Douglas Anderson, Director of the Laboratory for Circumpolar Studies

I am in the final stage of editing my book manuscript The Inupiat of Northwest Alaska over the Past Millennium to be published by Borgo Publishing. The book is an analysis of 70 years of Brown University’s archaeological and ethnographic research on the Inupiat—the people who have inhabited the coastal and riverine areas in Arctic Alaska for well over a millennium and who have roots in the region possibly going back at least 10,000 years.

The Haffenreffer Museum houses thousands of archaeological artifacts from these excavations and has been designated a national facility to curate the collections for the U.S. National Park Service. The collections, open to and utilized by researchers worldwide, have also been on display in a number of the museum’s exhibitions over the years and have been used in teaching Brown’s undergraduate and graduate students from the Department of Anthropology. Currently, plans are in the works, funded by the National Park Service, to upgrade the laboratory’s research and storage facilities. I and my colleagues are also completing the cataloging and organizing the museum’s Alaskan archaeological collections to meet current curatorial standards for the Department of the Interior.

Wanni Anderson, Museum Research Associate

I am completing my monograph Inupiat by the Sii under review by the University of Alaska Press. It is an historical ethnography of the people of Selawik, Alaska, where I and Douglas Anderson have spent numerous seasons, including one full year, conducting research. The monograph presents an Inupiaq Eskimo community living along the Selawik River, a major fishing river in Northwest Alaska. The people of Selawik were living in scattered households along the river and adjacent lakes until 1908 when the U.S. Government established a school and (Quaker) church to consolidate and settle the people as a village. From 1908 forward the village has grown to over 800 residents, the largest riverine community in the region.

This book is follow-up of my and Doug Anderson’s book Life at Swift Water Place: Northwest Alaska at the Threshold of European Contact published two years ago by the University of Alaska Press, and two earlier books on the folklore of the region: The Dall Sheep Dinner Guest: Inupiaq Narratives of Northwest Alaska and Folktales of the Riverine and Coastal Iñupiat. These last two books published with Inupiat Ruthie Tatqaviñ Sampson for the Northwest Arctic Borough and the National Endowment for the Humanities serve as bilingual English/Inupiaq textbooks for 11 Inupiaq village schools in the Northwest Arctic Borough School District.

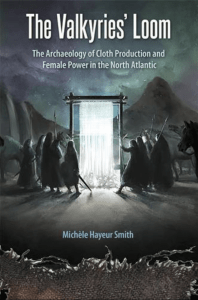

The Valkyries’ Loom: The Archaeology of Cloth Production and Female Power in the North Atlantic

Michèle Hayeur Smith, Museum Research Associate

My new book The Valkyries’ Loom is the culmination of nine years of archaeological research supported by three consecutive grants provided by the National Science Foundation’s Arctic Social Sciences program. The focus of these grants, which totaled more than $2 million, focused on the roles of women in the Norse colonies of the North Atlantic and their frequently ignored social position. Much of the archaeology in that region focuses on achievements,

institutions and activities associated with men with little attention paid to the lives, contributions, achievements, and institutions linked to the other half of the population. Through the analysis of items created by women it has been possible to “find women” archaeologically and create a more gendered archaeology of the North Atlantic.

This book addresses ideology, gender, and the role of women as members of society who are under-represented in studies of the North Atlantic region but whose agency, economic roles, and creativity produced important responses to climate change and resistance to colonial domination in the North Atlantic. The book showcases the underlying power and control which women were able to exert in these patriarchal societies by focusing on textiles, a often-neglected form of material culture that had been viewed by archeologists as void of any significance, but that actually gives us direct insight into what women did, what they made, and how their work was connected to local, national, and international interactions.

The Valkyries’ Loom spans roughly 1000 years, and is divided into sections, with an introductory chapter dedicated to the symbolic significance of weaving and textile production in Scandinavian societies from the Viking Age (ca. 750-1050 AD) to the 1800s. Since textiles uses and manufacturing strategies changed very slowly over time, major changes in its production are indicative of transformations occurring externally and impacting subsistence strategies. For example, climate change, colonialism, contact with mainland Europe or lack thereof prompted modifications in the use and fabrication of cloth.

From the Early Medieval (1050-1250) period into the 1600s, textiles were used as a form of currency in Iceland and were the core element in a structured barter, or commodity economy that was ultimately based on the value of units of silver. When contacts with Europe slowed after 1000 AD and the flow of silver into Iceland decreased, Icelanders turned to cloth as their unit of measure for all economic transactions. We see this archaeologically in the household production of extremely standardized forms and measures of cloth across the island.

This pattern was not duplicated across the North Atlantic. In Greenland cloth was produced primarily for household uses from the island’s settlement around AD 990 until its abandonment by the Norse around 1450. However, with the onset of the Little Ice Age, Greenlandic women changed their weaving styles to make cloth that was resistant to increasingly colder conditions. Rarely does one observe agency on such a personal scale in the archaeological record.

Other measures were also implemented in Greenland. The fur of Arctic animals and increasing quantities of goat hair were woven into their cloth as the climate deteriorated. Goats were better suited to the harsh Greenlandic environment than sheep and these changes in fiber usage document Greenlandic women’s resilience, creativity, and ability to adapt to major changes.

In the later medieval (1250-1550) and Early Modern periods (1550-1800) increasing numbers of imported European textiles appear in the Icelandic archaeological record and by the 18th century textile production was taken over by colonial overlords seeking to maximize profit from the North Atlantic’s minimal resources. Weaving workshops run by men were established as part of a Danish trade monopoly in Iceland, yet we see archaeologically that women resisted these impositions and continued to produce most of the island’s cloth on their traditional warp-weighted looms.

I am currently working with Alexandra Sanmar and colleagues across northern Europe on a new edited volume looking at the less well-known roles of women in northern societies. The Hidden Lives of Viking Women will explore roles that women held, but do not fit with stereotypical roles as housewives and mothers, including women as warriors, magicians, and lawyers, mythically important Valkyries, as well as men who were treated as women and women who occupied men’s roles. This new volume will be published with University Press Florida in spring of 2023.

All photos courtesy the authors | Cover Photography by Juan Arce