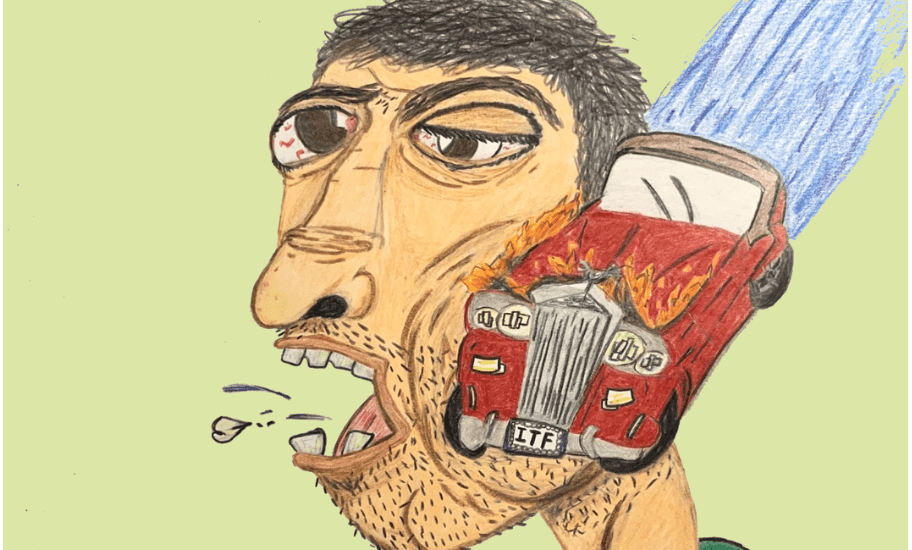

Illustration by Raphel Awa

Article by Arenal Haut

About 1.35 million lives are cut short every year due to road traffic injuries, “the leading killer” of people between 5 and 29 years old.1 An additional 20 to 50 million people suffer injuries every year.2 Death on the Roads, a data visualization tool by the World Health Organization (WHO), provides a sobering perspective. The center of the web page showcases a countdown clock, reading “A road user will die in: ”. Every 23 seconds, the timer restarts, and the death totals for today, this month, and this year rise with the latest casualty. It’s impossible to watch these real-time updates and not feel compelled to do something.3 Road traffic systems, described as “the most complex and the most dangerous” system impacting people’s daily lives, are treacherous, but they don’t have to be.4 These deaths and injuries are inequitable, overlooked, and preventable.

Inequity due to socioeconomic status, both between and within countries, is a significant source of road traffic disparities. Worldwide, 93% of road traffic deaths happen in low- and middle-income countries, yet these countries have only 60% of the world’s vehicles.2 Rates are highest in Africa and Southeast Asia, at 26.2 and 20.7 deaths per 100,000 respectively, and the rates have only been increasing. From 2013 to 2018, 27 out of 28 low-income countries saw an increase in road traffic deaths.1 Even within countries, people with lower socioeconomic statuses are the most likely to be involved in traffic incidents.2

Oftentimes, low-income populations are put at risk by their mode of transportation. The cheapest modes of transit relied on by many poorer communities are the highest risk. Pedestrians, cyclists, and motorcyclists are particularly vulnerable road users, and they make up more than half of all road incident deaths.2 Public transport is also perilous. Buses in Lagos, Nigeria are known by locals as danfos, ‘flying coffins’, or molue, ‘moving morgues’, but the poorest people have no other options.5 Ojo Iwonseyin, who commutes via the Lagos bus system, said, “Many of us know most of the buses are death traps, but since we can’t afford the expensive taxi fares, we have no choice but to use the buses.”6

Transportation is a social determinant of health, and public health should be addressing it within that framework. Despite the fact that road traffic injuries kill more people than HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, or diarrheal diseases, public health efforts continue to ignore the impact traffic deaths have on our world and our communities.1 Described as “the neglected epidemic,” the pattern of traffic-related fatalities and injuries garner minimal media attention, despite their significant health impacts.5

The worst part of these fatalities is that the vast majority are preventable. Research has clearly shown that targeted efforts, such as enacting and enforcing traffic legislation, have positive health benefits.7 Yet globally, policy efforts on this topic have been minimal.5 The WHO has identified five key legislative categories for road safety action: speed, drunk-driving, motorcycle helmets, seat belts, and child restraints.1 Many countries lack laws that meet these minimum safety standards. and even when such laws exist, they are often poorly enforced due to “inadequate resources, administrative problems, and corruption.”5 Inadequate licensing, both of drivers and their vehicles, is also common due to systemic failures.5 In Lagos, Nigeria, for example, most bus drivers drive unroadworthy buses and regularly break traffic laws.6

After a crash occurs, poor health infrastructure and inaccessibility of healthcare contribute to worse outcomes. Medical costs remain exorbitant, and these costs are an additional barrier to care, particularly for the low-income populations most vulnerable to road-traffic-related injuries and death. In Ghana, for example, only 27% of people injured in traffic incidents used hospital services, which is in large part due to the financial barriers.5 We must continue to strengthen healthcare systems in every country with the goal of making healthcare affordable and accessible for all. Though not a solution in isolation, this work can minimize one of the barriers facing global citizens today.

Transportation is just one sector where we can employ the Health in All Policies (HiAP) approach. With collaboration and a focus on structural determinants of health, we can understand and address the societal factors that contribute to inequities. By strengthening systems, particularly those frequently perceived as irrelevant to health, we can minimize the impacts of traffic crashes and improve outcomes across the world. Road traffic deaths disproportionately impact those with lower socioeconomic statuses, and we must act in the interest of health equity.

This isn’t a new conversation. In 2004, the UN Road Safety Collaboration (UNRSC) was created, and the establishment of projects such as the Global Road Safety Initiative (GRSI), the Global Road Safety Facility (GRSF), and the Bloomberg Philanthropies Initiative for Global Road Safety followed soon after.8-11 Community organizing around road safety has been going on for much longer. Protests such as “parent and baby-carriage blockades” were documented as early as 1949 and remained common through the 1950s and 60s.12 This organizing intersected with other activist movements, and groups like the Black Panthers and various disability rights groups were involved in road safety actions.13 Road safety has always been a social justice issue.

Today, we are two years into the Decade of Action for Road Safety 2021-2030, developed in collaboration by the World Health Organization, the UN Regional Commissions, the UN Road Safety Collaboration, and other partners.14 In less than a month (May 15th-21st), the UN is holding its 7th biennial Global Road Safety Week.15 But these efforts have garnered minimal attention within the public health field, let alone any broader media coverage in the public eye.

So let’s return to the timer mentioned at the beginning of this piece.3 At an average reading speed, this article has taken you less than four minutes to read. In that time, an estimated ten people have died due to a road traffic accident. Road safety and

legislation may seem dull, but safer roads save lives.1 Investing in traffic systems, particularly in low- and middle-income countries, has the potential to have a major positive impact. The most vulnerable members of our global community are suffering, and their deaths are preventable. Our action is required to work towards health equity.

REFERENCES

- World Health Organization.; 2018. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/277370/WHO-NMH-NVI-18.20-e ng.pdf?ua=1. Accessed April 14, 2023.

- World Health Organization. Road Traffic Injuries. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/road-traffic-injuries. Published June 20, 2022. Accessed April 14, 2023.

- World Health Organization. Death on the roads. World Health Organization. https://extranet.who.int/roadsafety/death-on-the-roads/. Published 2018. Accessed April 14, 2023.

- Peden M, Scurfield R, Sleet D, et al., eds. World Health Organization: Social Determinants of Health Team; 2004. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/world-report-on-road-traffic-injury-preventi on. Accessed April 14, 2023.

- Nantulya VM, Reich MR. The neglected epidemic: road traffic injuries in developing countries. BMJ. 2002;324(7346):1139-1141. doi:10.1136/bmj.324.7346.1139

- Ibagare E. On the buses in Lagos. BBC News. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/1186572.stm. Published February 28, 2001. Accessed April 14, 2023.

- The World Bank Group. Public health at a glance: Road safety. The World Bank. http://go.worldbank.org/PN670SJ790. Published 2009. Accessed April 14, 2023.

- UN Road Safety Collaboration (UNRSC) . United Nations Road Safety Collaboration: About us. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/groups/united-nations-road-safety-collaboration/about. Published 2023. Accessed April 14, 2023.

- Global Road Safety Initiative (GRSI). Global Road Safety Partnership (GRSP). https://www.grsproadsafety.org/programmes/global-road-safety-initiative/. Accessed April 14, 2023.

- About Us: What is GRSF. The Global Road Safety Facility. https://www.roadsafetyfacility.org/about-us. Accessed April 14, 2023.

- The Bloomberg Philanthropies Initiative for Global Road Safety. Bloomberg Philanthropies.https://www.bloomberg.org/public-health/improving-road-safety/initiative-for-globa l-road-safety/. Accessed April 14, 2023.

- Norton P. The hidden history of American anti-car protests. Bloomberg.com. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-10-08/the-hidden-history-of-amer ican-anti-car-protests. Published October 8, 2019. Accessed April 14, 2023.

- Fermoso J. The long history of protesting for safer roads in Oakland. The Oaklandside. https://oaklandside.org/2022/10/21/traffic-safety-protests-oakland-rapid-response-team/. Published October 21, 2022. Accessed April 14, 2023.

- Global plan for the decade of action for road safety 2021-2030. World Health Organization.https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/global-plan-for-the-decade-of-action-for-r oad-safety-2021-2030. Published October 20, 2021. Accessed April 14, 2023.

- 7th UN global road safety week: 15-21 May 2023. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/campaigns/un-global-road-safety-week/2023. Accessed April 14, 2023.