In the ongoing series, the Museum’s collection team shares stories emerging from their current work on two inventory projects funded by the Mellon Foundation: “Engaging the Americas” and “Transforming the Haffenreffer.”

Read the original posts on the Haffenreffer Museum’s website, linked here.

Bottle Cleaning and Storage

Lauren Banquer, Collection Assistant

These Haffenreffer & Company beer bottles have been in the collection for many years, unopened. In preparation for the museum move, the bottles needed to be cleaned and rehoused for safe transport.

These Haffenreffer & Company beer bottles have been in the collection for many years, unopened. In preparation for the museum move, the bottles needed to be cleaned and rehoused for safe transport.

I removed the bottle caps using a quarter and a wing corkscrew. This prevents the lever from creating a crease across the top. A few light pulls upward around the sides in different spots also prevents the teeth from flaring out.

Once the bottle caps were removed, the bottles needed to be emptied and cleaned. Because of the continued fermentation and oxidation of ethanol in the bottles, malt vinegar was produced. The liquid was easy to pour out; however, a slimy, black coating formed (a glob of yeast and bacteria common in fermentation processes, like in Kombucha) that was a bit more difficult to remove.

First, I rinsed the bottles with warm water to break up some of the scoby. I was careful not to let water drip on bottle labels in order to preserve them. I used distilled water to break up the residue and made cotton swabs to wipe them clean. For extreme buildup, I let distilled water sit inside for thirty minutes before rinsing again with warm water.

For rehousing, I created an interlocking grid so the bottles would be separated and contained. The top rows of ethafoam lift off, making it easier to access individual bottles. Each bottle also has a small mount in order to prevent movement and tipping within the grid.

I was curious about the Haffenreffer brewing history, and did some research to place these bottles in context within the collection. Rudolf Haffenreffer, Sr. was a brewer, maltster, and barrel-maker who worked in Germany and France before immigrating to Boston in 1868. He established Boylston Lager Beer Brewery in 1871 which eventually became Haffenreffer and Company.

Rudolf Haffenreffer, Jr. was also interested in brewing; attending the U.S. Brewers Academy in New York and completing Fermentation courses at MIT. He founded Old Colony Brewing and later took control of King Philip and Enterprise breweries before moving to Bristol, RI. Haffenreffer Brewing Company survived Prohibition by switching production to low-alcohol beers. Afterwards, Haffenreffer, Jr. became president and chairman of Narragansett Brewing Company. Later, he licensed several beers to Narragansett when the company closed in 1965.

Sorting through the 7771s

Jessica Nelson, Curatorial Assistant

Why would one artifact number be assigned to multiple objects? During the inventory process, the idiosyncrasies of previous collectors and historical museum and archaeological practices come to light, like the use of a single object number for groups of artifacts that were donated to the museum at the same time. The records for object 7771 indicate that there are some seven hundred projectile points with this number!

Why would one artifact number be assigned to multiple objects? During the inventory process, the idiosyncrasies of previous collectors and historical museum and archaeological practices come to light, like the use of a single object number for groups of artifacts that were donated to the museum at the same time. The records for object 7771 indicate that there are some seven hundred projectile points with this number!

The group of objects numbered 7771 includes projectile point types that range throughout the Archaic Period. They all were collected from what is currently recognized as the state of Massachusetts and donated to Rudolf Haffenreffer as part of the Bigelow collection in the early days of the Museum. As you can see from the small subset in the photographs, these points range in size, shape, and material. As a result, I am assigning individual object numbers to each of the 7771s in the collection. I am also updating the database records with the goal of making sure that each specific 7771 point is differentiated and accessible in the future.

Field Collections – A Bigger Picture

Patricia Duany, Collection Assistant

Field collecting has been a practice at the Haffenreffer Museum since the early days of the museum –– even before being part of Brown University. By lending support to students and professors, both Brown-affiliated and otherwise, researchers are able to acquire objects, conduct interviews, and research diverse global cultures, later accessioning the objects and notes into the museum’s permanent collection.

Field collecting has been a practice at the Haffenreffer Museum since the early days of the museum –– even before being part of Brown University. By lending support to students and professors, both Brown-affiliated and otherwise, researchers are able to acquire objects, conduct interviews, and research diverse global cultures, later accessioning the objects and notes into the museum’s permanent collection.

A wonderful example is a field collection of needlework material from the Azores, collected by Anne Page McClard and Ken Anderson in 1991. Buoyed by copious notes and interviews, the collection comprises over 130 beautiful crochet, lacework, and other traditional textiles from Azorean artisans, raw materials such as thread and flax, in-process samples and finished items, and the original tools used including a tiny marine ivory crochet needle –– made by the artisan’s grandfather in the traditional way.

Recently inventoried during the textile boxes inventory phase, the Azores collection highlights the process of making these delicate and intricate laces and details the artisans’ stories, demonstrating how field collections can provide a larger context to practices and crafts throughout the world.

Ask Thierry

Dawn Kimbrel, Registrar

One of the goals of the Mellon inventory project is to gain better physical and intellectual control of the collection. Condition assessments will allow the collection team to pack and move objects safely. Enhanced documentation will allow the team to track location changes throughout the relocation process. Gradually new information becomes available to researchers, students, and a broader public audience through the online catalogue.

One of the goals of the Mellon inventory project is to gain better physical and intellectual control of the collection. Condition assessments will allow the collection team to pack and move objects safely. Enhanced documentation will allow the team to track location changes throughout the relocation process. Gradually new information becomes available to researchers, students, and a broader public audience through the online catalogue.

When the Collection team comes across an unidentified object in the collection or a missing storage location, they voice a common refrain, “Ask Thierry.” Thierry Gentis, Curator, has a good memory; he holds institutional knowledge acquired over the past forty years. Thierry will help sort out problems. The rhythm of the “Ask Thierry” dialogue goes something like this:

Q: Have you seen the whereabouts of the interior wall of a Tuareg tent?

A: “Look on the north wall. I remember rolling it and placing a picture on the outside. It’s very large and is used for special occasions like weddings.”

Q: Would you help sort out the accession number for this African vessel? It’s too heavy to move.

A: “Look at the photographs from the gift from William Simmons received in 2000. You will find it there.”

Q: Do you know what happened to the Deed of Gift for this figure?

A: “I’ll find it, don’t waste your time.” Thierry evaporates, then moments later a file mysteriously appears on the workspace.

An Example of Indigenous Repair Using Local Materials

Rika Smith, Conservator

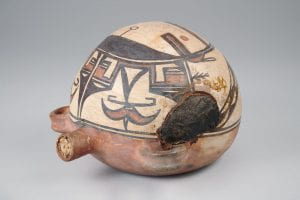

One of the goals of the Mellon Foundation’s grant to the Haffenreffer Museum of Anthropology is to carry out condition assessments of the collection to determine which objects will require stabilization treatment before packing to prevent damage during the move to Providence. Conservator Rika Smith recently began the condition survey of 1,000+ pottery objects, including some from the American Southwest. One Hopi water canteen with a remarkable indigenous repair also revealed the use of a local plant product as a cork.

This large Hopi water canteen dating to the mid-19th century was damaged and sustained a significant hole in its side. The canteen must have been a much-valued object because it was repaired with a large waterproof plug made from pine pitch. The Hopi also use pine pitch to waterproof pots and to mend cracks.

Natural materials such as leaves, fibers, and fabrics were also used as corks. A small corn cob wrapped in cotton cloth served as the cork in this canteen.

Sustainable repairs from local natural materials!

Cover photography by Juan Arce