Close-up and Personal – Using the Haffenreffer Collection as a Teaching Tool from the Perspective of a Teacher and Maker

Barbara Seidenath, Senior Critic, RISD Graduate Program in Jewelry and Metalsmithing

In my teaching practice, I consider learning from objects an indispensable tool for a successful learning outcome. My course ‘History of Adornment’ (JM4440-01) is designed to foster a deeper understanding of jewelry traditions in non-Western and Western cultures. We discuss topics ranging from personal ornament being a universal form of human communication, the placement of value, to technology, innovation and exchange. The students are asked to conduct original research on contemporary and historic ornamental traditions.

As my students are working towards becoming makers and designers, I regard the experience of studying objects related to their field of interest of utmost importance. Through researching a different culture or time period, the students are able to develop a deeper understanding of the historical and political contexts within which these objects were created and used.

Studying the actual objects under the guidance of curator Thierry Gentis allows them to experience the physicality, scale and even spiritual presence of the pieces. Students often start by reflecting on their own practice and discuss their own cultural context in which they create jewelry and objects. Important for the young makers is that they are also able to study observe the traces of the hand and tools close-up and this experience allows them to form a meaningful connection to different makers that builds awareness and encourages further learning.

Over the past decade, the class has culminating in a field trip to either the Collections Research Center facility housed in Bristol or a class visit to the CultureLab in Manning Hall on Brown’s campus facilitated by curator Thierry Gentis. This has become a much anticipated and invaluable part of the learning experience in my course.

During the pandemic, Thierry and I took on the challenge of developing creative new ways to utilize the collection virtually for study purposes. We established that the extensive collection of West African objects would be ideal for the discussion of a range of topics related to the specific class segment concerned with the correlation of geography, environment and resources on forms of lifestyles and production on the African continent.

After establishing the premise, we selected objects from Ashante and Akan people in West Africa. Dawn Kimbrel, Haffenreffer registrar, was very helpful in creating an online Highlights folder for our class on the museum’s online catalogue. Students were introduced to the West African cultures by visuals and two readings about Wgold and the Ashante and Akan kingdoms in Ghana. They were then asked to select two pieces from the Highlights folder, research those objects and bring one or more questions to the discussion.

The objectives were as follows:

- Become familiar with the meaning and context of gold ornaments and related objects from the Ashante and Akan kingdoms in West Africa .

- Research two objects from the Highlights folder in the online Haffenreffer Museum of Anthropology and Research Collection.

- Write a brief paragraph stating the reasons you to chose thes object and what you found out about it in your research .

- Prepare a question for discussion with curator Thierry Gentis to be submitted prior to our meeting.

Our project concluded with a virtual visit via Zoom in which students engaged Thierry in a lively discussion of the objects. Even without the opportunity to interact with the physical objects, this modality still provided a meaningful learning experience.

The pandemic has provided a valuable experiment on how the collections can be used effectively in new ways. However, it has also revealed that nothing can replace a field trip to the Collections Research Center in Bristol or a visit to CultureLab where the students can get hands on experience with objects. I would like to thank Thierry Gentis and the team at the Museum for the generous support they provide.

The Art of Craft

Robert Ward, Assistant Professor of the Practice, Nonfiction Writing Program

No ideas but in things. These words, from William Carlos Williams’s poem Patterson, are the epigraph to a new course in the Nonfiction Writing Program, The Art of Craft. In designing this course, my aim was to encourage students to explore the intimacy between the traditional skills of manual labor – of the potter, the woodworker, and the quilter – and the style, form, and textures of their creative prose. With this aim in mind, Leah Burgin, then the Manager of Museum Education and Programs, and Thierry Gentis, the Curator, helped me select two items of pottery, which they presented to the class via Zoom. The first was a Peruvian Quero (98-3-1), in dark wood, made between 1600 and 1700. The second, joni chomo, (2013-13-1), was a clay vessel made during the twentieth century by the Conibo People of Peru. Due to the fifty-minute class time, and also due to the students’ fascination and questions, we focused most of our attention on the first item.

As I write, I am looking again at this Quero, and how Thierry and Leah helped us to reflect on its presence, its history, and its materials. It displays on its body a procession of people with various ceremonial hats, with flowers and fruits adorning the foot, the gorgeous tones of red and gold. The students were also fascinated by what looked to be a chip, the faded rim, the wide fluted out lip, all testament to its use and to its beauty. The presentation was inspiring for all of us. Afterwards, I created an assignment that asked students to find an artifact on the Museum’s online catalog, one that especially moved them, and to write an essay shaped by its symmetry. I am still impressed by what the students came up with, which were formed by using narrative vignettes, scenes, images, musical scores, and verse.

It isn’t easy to build a bridge between a vessel and a written story. But it can be done, of course, using quality materials, care, and pride in our workmanship. Stephen Greenblatt, in an insightful article given to me by Leah, helps us think of this bridge in two ways. The first he calls resonance, “the power of the displayed object to reach out beyond its formal boundaries to a larger world.” The second is wonder, “the power of the displayed object to stop the viewer in his or her tracks, to convey an arresting sense of uniqueness, to evoke an exalted attention” (42). Resonance and wonder, but also use, story, presence, shape, and beauty. These words come quite naturally from our appreciation of craftsmanship, whether that is of a wooden pot, a manuscript, or an oak cabinet.

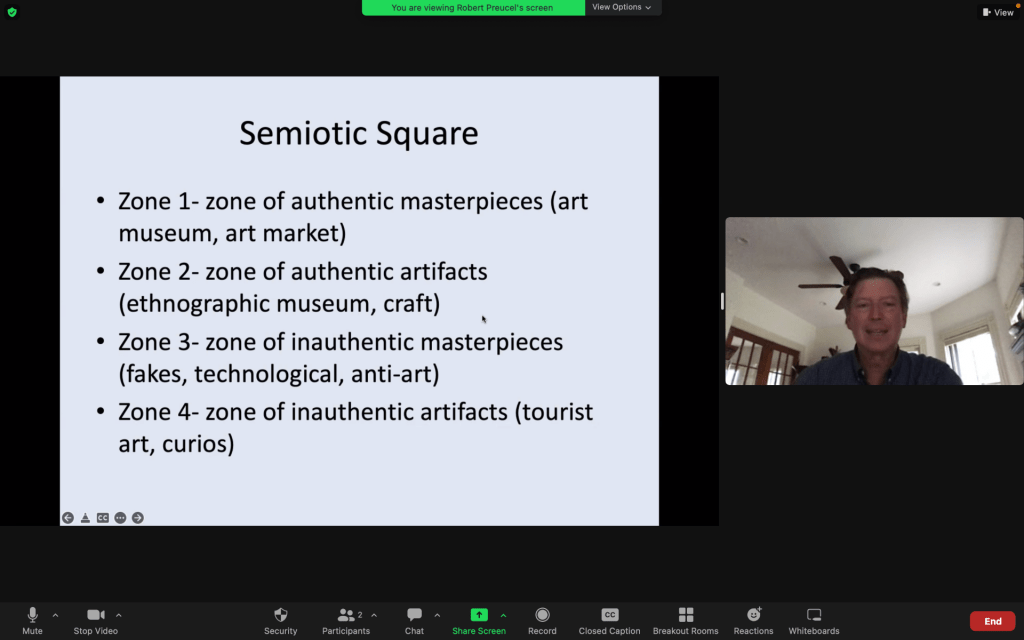

Teaching Museum Anthropology During COVID

Robert W. Preucel, Director

According to Flora Kaplan, Professor Emerita and founding director of the Museum Studies Program at New York University, museum anthropology can be defined as anthropology practiced in museums and the anthropology of museums. Each research area crosscuts the other, but is nonetheless the product of different histories. Christina Kreps, Chair of the Department of Anthropology and Director of Museum and Heritage Studies, at the University of Denver, has elaborated on this definition. She explains that anthropology in museums is the application of anthropological methods, theories, and insights to the documentation, study, care, representation, and safeguarding of people’s tangible and intangible culture. Anthropology of museums is associated with postmodern, postcolonial and Indigenous critiques of museums as Western institutions. It has given rise to the “new museum theory” and “critical museology.”

This framing has been important in the teaching of museum anthropology at Brown University. Shepard Krech with Kevin Smith, developed their course “Anthropology in/of the Museum,” and it has been taught by a number of Postdoctoral Fellows over the years. I have revised it, but entirely within the spirit of their vision. Students explore both the history of anthropology museums as well as the emergence of the new museology, critical museum studies, repatriation and restitution, and decolonization. I taught it twice during the pandemic. The first time (Spring 2021) was entirely online and the second time (Fall 2021) was in person, but masked.

I have five learning goals for my students. I seek for them to:

- gain knowledge about the origins and history of museums as public institutions,

- develop an understanding of the changing roles of museums in response to new movements for social justice,

- explore the power of objects as “mediators” of social relationships,

- learn about approaches to the care and stewardship of objects from different cultural perspectives, and

- learn about careers in museums.

Teaching museum anthropology during the Covid-19 pandemic has been a valuable learning experience about pedagogy. It has posed some real challenges, especially when it was impossible to interact with one-another in person or to visit local museums. But it has afforded new opportunities such as enabling creative projects focusing on museums’ digital resources and facilitating access to scholars at other institutions.

Because we were unable to visit museums in person, we did the next best thing- namely, visit them virtually using their websites. I reconceptualized several class exercises to take advantage of this process. As an example, I asked students to select an object in an anthropology museum and compare and contrast how its catalogue description compared to a similar object in the collections of a natural history museum and an art museum. The idea here was to identify and critique the classificatory systems that we take for granted. In another exercise, I asked students to evaluate the acquisitions policies of anthropology, natural history, and art museums. This exercise gave insights into how ethical issues are handled by different kinds of museums.

I also wanted to introduce students to museum professionals. So I invited my Haffenreffer staff to participate in my class and persuaded several colleagues from other museums to zoom in. My staff spoke on collection management (Dawn Kimbrel), exhibition design (Kevin Smith, Rip Gerry) and education/public outreach (Leah Burgin, Leah Hopkins). In my spring class, I invited Lucy Williams and William Wierzbowski (Penn Museum) to speak on Tlingit potlatch loans and Dwaune Latimer (Penn Museum) to speak on Benin bronzes. I also invited Lorén Spears (Tomaquag Museum) to discuss the Tomaquag Museum and Darren Ranco (University of Maine) to talk about decolonizing museums. In the fall, I invited Patricia Capone (Peabody Museum) to speak on repatriation and T. Rose Holdcroft (Peabody Museum) to talk about conservation.

The students seemed to enjoy both iterations of the class. They liked the online projects and the chance to look at objects in new ways. But I think they especially appreciated engaging with a range of museum professionals and asking them questions about their career trajectories and life stories. One encouraging sign for the profession is that after both classes several students approached me for advice on internships at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the RISD Museum, and the Whitney Museum. They are our future!

Cover photography by Juan Arce