The thinner-walled buildings that take up the central and southeastern parts of Uronarti’s interior are interpreted as housing for the population who lived there. All of these buildings, which share walls with one another, were laid out on the same plan initially, with differences only where the irregular shape of the fort demanded it. From the street one entered a longitudinal hall. This led into two back rooms, parallel to one another and perpendicular to the hall. Recent work suggests that while the fort was entirely covered with buildings in plan – a sort of 1:1 scale blueprint – the construction of these houses may not always have occurred at the same time or even to the same plan.

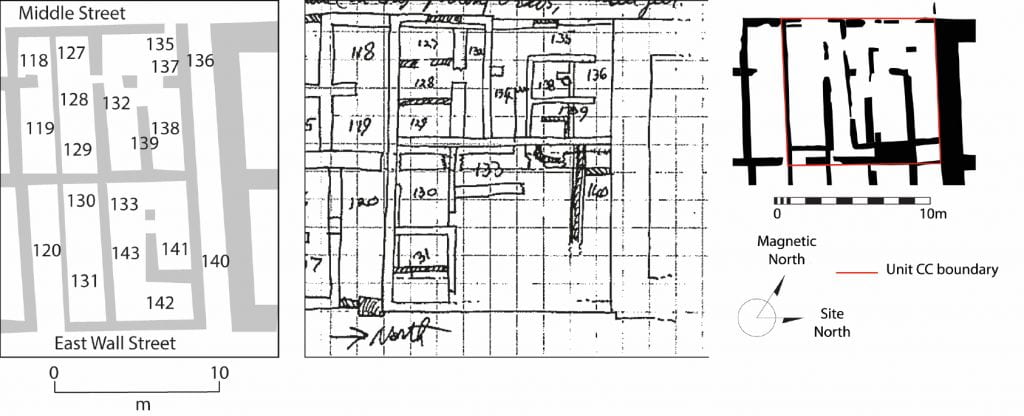

Composite image showing the current state and original plan of the barracks in the north of the fort. The blue is the corner of the treasury complex. Black is the first phase house layout within our Unit CC. The grey overlay shows how that plan was repeated to form the whole of the barracks area. As can be seen, however, there are walls that do not match the lines. Do they represent later major modifications, or were the houses simply not built on the original plan? Our interpretations are as dynamic as life in mudbrick structures.

The basic three-room plan of the initial layout is amongst the simplest versions of a type of house known from other state-planned Middle Kingdom settlements. Like so many other times and places where housing is built on the orders of an organization, not its occupants, the picture presented would have been one of sameness, familiarity from house to house. When houses deviated from the plan, which is what we are tracing, the monotony diminished.

As of 2019, we have excavated two areas of housing in the barracks. Our first interpretation of the substantial discrepancy between the 3-room layout and the walls we saw in the north, in our unit CC, suggested to us major modification of a structure over time. However, some of what we found closer to the middle of the fortress, in our unit FI, made us rethink the process of construction and occupation at Uronarti. We are now no longer so certain that the houses were actually built as laid out in all cases, though we remain convinced that many barracks areas saw substantial modification after their original construction.

Unit CC:

Unit CC was excavated in 2015-16 in the northernmost area of the originally uniform housing. We chose to begin our excavations here because we could see that modifications had been substantial, with walls blocking off the street between the barracks and the granary area to incorporate the space into a house. We also saw evidence that suggested reconfiguration of a 3-room house into something larger and more labyrinthine.

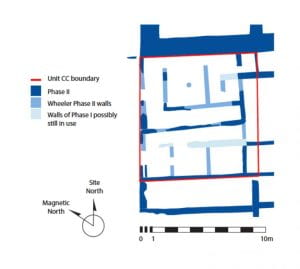

Both the building history and the excavation history complicate our ability to figure out the phasing of domestic architecture at Uronarti. Left, the published plan of the area in which our Unit CC was excavated. Middle, a scan from Wheeler’s notebook. Right, our unphased plan of remaining walls.

Interpreting the remains to produce phased plans in which we have confidence is difficult. We know that the Phase II architecture was complicated, different than Phase I, and not standardized across the site, but precisely what it looked like is more debatable. We now dispute whether Phase I walls were ever standing in this area and suggest they might have been laid out in plan but never built.

One thing that confused us when we dug unit CC was how totally the plans of the two most obvious phases differed, yet how easy it was to see both. We had everywhere stubs of walls on the 3-room plan. In some cases, the second phase walls were built on top of those stubs. In some they were built close to but not on top of them, so close that had both walls been standing at the same time the space between them would have been awkwardly unusable. We determined that the first phase walls throughout this area must have been everywhere very low at the time of the second phase building. This would not be expected in the major remodeling of a house unless it were completely destroyed before building anew. This was how we first interpreted the remains: first a 3-room house, then the destruction of that house down to the wall stubs, then the construction of a house on a totally different plan.

We knew that the plan of the final phase of Unit CC did not look anything like the bureaucratic stamp of the earlier phase. Was this an individual decision of a particular unit of people living in this house, or does it show a changed relationship between state and fortress?

We knew that to get a better handle on the phases of construction and use and what they meant in the barracks we would need to target those areas with substantial modifications, especially those where there were walls built that defied the 3-room blueprint. These places interest us for two reasons – first, they’re the most substantial changes in the plan of whole structures, but second, they are also the only places where intact stratigraphy remains after Wheeler’s excavations. (The banner image for this page shows one such place.) They might give us a chance to glimpse the deposits in the rooms from the time of their original configuration.

Unit FI

In 2018-19 we opened a unit in a house close to the middle of the fortress. Its front hall opened onto the main street of the fortress, and it preserved the classic plan in its walls, some of which were still standing above waist height.

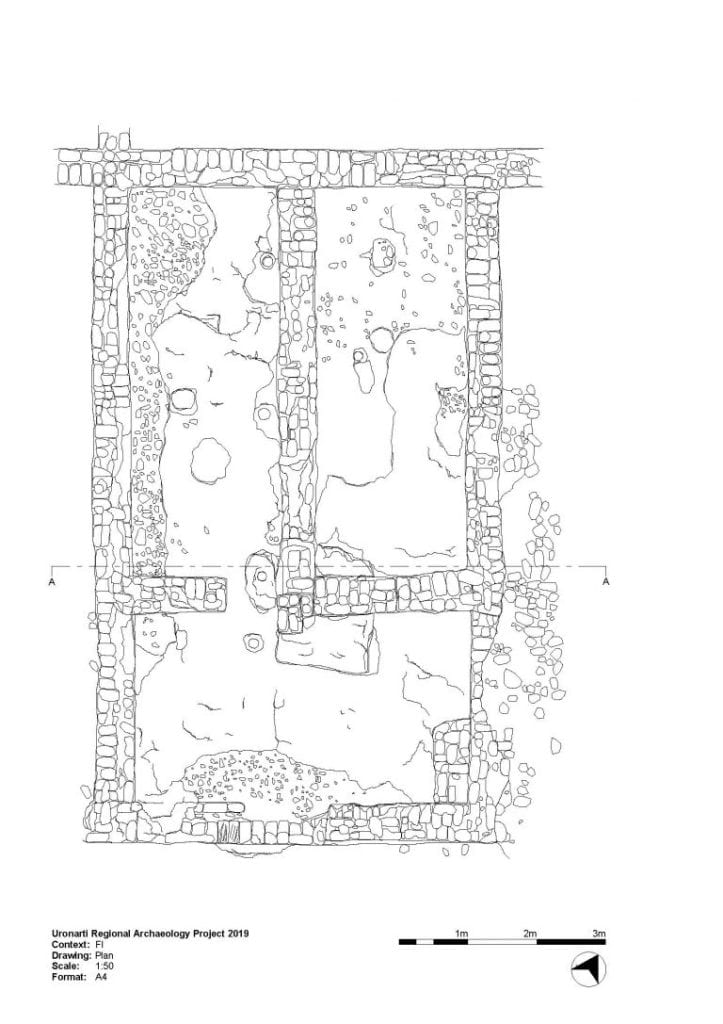

Plan of the house excavated in Unit FI.

This specific house was chosen because the doorway between the front hall and the northern of the back rooms showed substantial modifications: it had been narrowed at one phase, and entirely bricked up at a later phase. (It looks like a solid wall on the plan above.) Because Wheeler’s quick work had left walls intact, particularly walls on the expected 3-room house plan, this was a later phase he had not removed. It was archaeological gold! Beneath that later blocking was over a meter standing of intact untouched stacked floors, one on top of another. It was eroding from year to year, and we knew our time to excavate it was running out.

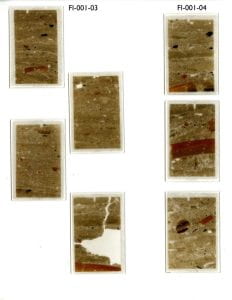

The preserved stratified floors beneath a later doorway blocking in Unit FI, looking southeast.

We tackled the floors in two ways. First, we took samples about the size of bricks from the preserved stratigraphy, carefully carving out and wrapping in plaster bandages vertical slices that overlapped each other, so we were sure to sample every layer. These have now been consolidated and sliced into thin sections so we can look at them under the microscope. They will be analyzed to help us understand the processes that led to the formation of the floors, from intentional plastering to trampling by animals, as well as the activities that took place here. Even without a microscope we can see preserved grain, fish bones, and ceramic sherds.

Thin sections of the stratified floors from Unit FI prepared for micromorphological study.

Next, we excavated down from the top through each of the layers. In many cases they were not possible to see individually during excavation, so we arbitrarily dug in small passes and collected, sieved, and bagged the material separately. One particularly intriguing layer was loose and unconsolidated dust and pieces of mud brick. Unlike all of the trampled hard floors, this looked like rubble thrown in as a leveling layer, something we see elsewhere in the fortress associated with construction phases. In this case the layer had over 40 fragments of seal impressions, raising serious questions about the location of seal impression fragments throughout the fort and to what degree trash moved around after its initial deposit.

In addition to its blocked doorway, Unit FI presented us with another architectural detail of great importance: while its walls were all on the 3-room plan, they showed at least two major phases, and the first of those phases was very low and uniformly built. The earliest floors appear to predate the construction of the walls above this low first phase. It suggests to us that the house was laid out in plan, and the space used by occupants of the fortress, before the rooms were actually constructed. This has allowed us to reinterpret the remains of Unit CC, seeing perhaps not a major remodeling so much as a plan that was never realized, that was obsolete by the time that space came to be used for architecture. The relationship between town planning, town building, town occupation, and a town’s organic growth and change, is more complicated than we first realized.

Even clarification of architectural phases still leaves hanging one of the most fundamental questions about the barracks: who was living at Uronarti? Did the nature of its population change over time? When we use the word “barracks” we presuppose that the population was soldiers, but the architecture does not tell us this. After all, the type of house is similar to houses in places where the population was presumably a more ordinary urban mix. There is no reason the house type would not have worked for barracks – you could easily sleep five to ten men in each of the back rooms, using the front hall for more communal activities – but also no reason a family with children could not live in such a place.

Agate microliths used as arrow heads, found in Unit FI. The Egyptian Middle Kingdom arrow had a straight rather than a pointed striking surface.

Were there soldiers? Almost certainly: in FI we discovered a number of classic arrow heads, for starters, as well as a shaped round granite ball that may have been shot for a sling. But the soldiers did not polish their weapons all day, and some of the most remarkable finds from FI include fish skeletons embedded in floors as well as a number of weights, made of both stone and ceramic, that were probably used to sink fishing nets.

Food was unquestionably a major concern for whoever occupied these houses. Some amount of cooking probably happened outside of them – bread loaves appear to have been provided by the administration of the fortress, and bread was the chief staple of the Egyptian diet. But the front

Nubian cooking pottery is a small percentage of our total finds in excavation and survey at the fortress, but consistent.

halls might have been used for minor cooking, and FI suggests that fish processing was happening inside. A moderate presence of Nubian cooking pots in the fortress dumps suggests that some of the food preparation – and thus some of the people? – were more local than Egyptian, but the picture of ethnicity is particularly complicated at the frontier given that there were at all times “Nubian” populations even in Egypt, including in the army. Was there a servant population at Uronarti, and if so did they, too, live in these houses? (See also: Site FC.) When we see the major differences in the plans of houses in Phase II, is that because social units changed? Cemeteries at some of the other fortresses suggest that in the later Middle Kingdom the garrisons became more permanent and that women and children were parts of the communities living in them. This may have led to changes in house structure.