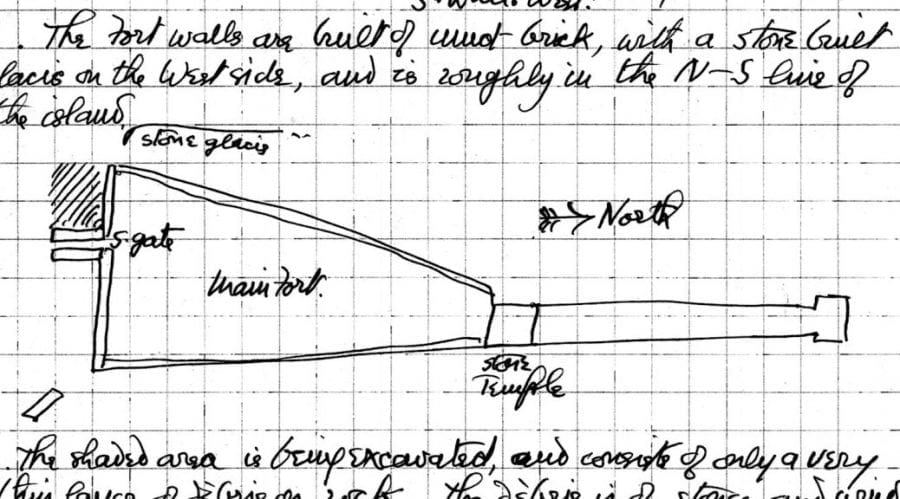

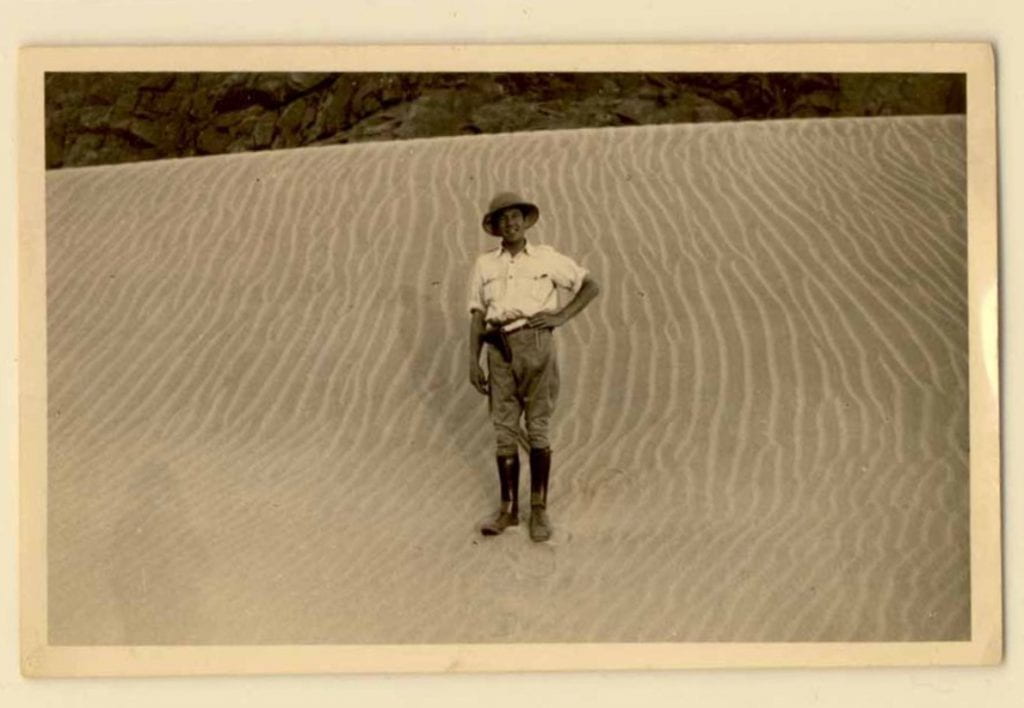

Uronarti was excavated in the 20th century as part of a larger mission led by George Reisner to uncover the fortresses of the Second Cataract region. The project was funded jointly by Harvard University and the Boston Museum of Fine Arts (MFA). The Uronarti crew, led by Noel Wheeler, travelled to site every day from several kilometers to the south. Wheeler’s original notebooks – which we’re fortunate to have access to thanks to the MFA – often have more extensive remarks about the car breaking down on desert tracks than about the archaeology.

Noel Wheeler, the first to oversee major excavations of Uronarti.

After a brief preliminary exploration in 1924, campaigns at Uronarti lasted from November 1928-January 1929, and from February-March 1930. In the four months of these two seasons the pace was frantic: the entire fortress was cleared as was much of the outer fortress; a small cemetery on Hill A that is now inaccessible was excavated; and the “campaign palace” was dug. The objects collected were split, and today are housed partly in Boston and partly in Khartoum.

The expedition also poked around on the southernmost hill of the island – Hill G – but notes on that were never published.

Neither Wheeler nor Reisner was involved in the final publication of the excavation records of Uronarti, Wheeler because he had left the project in some disgrace, and Reisner because he died before publication. Dows Dunham, then curator at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, wrote the volumes on the Second Cataract forts.

Dows Dunham on duty at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

While admirable and necessary, these volumes suffer for having been penned by someone who had not been part of the work itself. The publication as a whole focused more on the original foundation of the fortress than on the ways it was modified over the course of its use.

The legacy of the Harvard/MFA work is mixed and often frustrates us. Wheeler recorded relatively little, did not dig stratigraphically, and dumped on top of things we would still want to see. Since the volume of dump is very high, and since we – unlike Wheeler – collect all artifacts, excavating his dumps by modern methods would be a mammoth task. The publications are inadequate. The site was not backfilled and the fortress has suffered badly from erosion since. The published plans contain numerous inaccuracies. The notebooks and most of Reisner’s published work are disturbingly racist.

We assign each Wheeler room a context in our own recording system so that we can bring relevant records from his notebooks, the publications, and the objects as studied in the museums, into our own recording system (see Technology).

For all this – and it is much – we still benefit from the work Wheeler did. With modern methods, particularly in such a remote place, it would take lifetimes to excavate the whole fortress. The notebooks often allow us to figure out details, at least of architecture though never of deposits, that the publications leave opaque. We mourn the loss of nuanced data, but appreciate the big picture afforded by the early excavations. As much as the records allow, we incorporate Wheeler’s finds into our own project. We use his room numbers and create database records in our system for his excavation notes and the objects he found, allowing for searches that return both his finds and ours for analysis together.