Illustration by Punnava Alam

Article by Parisa Afsharian

The United States is facing an epidemic of chronic disease both inside and outside of its flawed carceral system. A 2011-12 study of state and federal prisoners reported that half of those incarcerated have a chronic health condition—including cancer, high blood pressure, stroke-related problems, diabetes, heart-related problems, kidney-related problems, arthritis, asthma, and cirrhosis of the liver—and this number has only increased in the last decade. Furthermore, there are higher rates of incarceration for Black and Hispanic populations—and by extension, racial and ethnic minorities are about two times more likely to have chronic diseases2,3. Thus, the epidemic of chronic disease and incarceration directly relates to the failure to abate health disparities. The first step to improving the health of prisoners of those within the carceral system and breaking cycles of chronic disease upon release is to improve the food that they eat each and every day. However, the current legal, economic, and political infrastructure for the enforcement and deployment of proper prison nutrition is lackluster and insufficient. The absence of proper nutrition in prisons is a human rights issue exacerbated by the inadequate and discriminatory policies governing access to nutrition both within the carceral system, and upon release.

The legal system governing nutrition standards at state and local carceral facilities is an amalgamation of state and local policies, along with a myriad of court decisions. There exist few all-encompassing prison food laws. Namely, The American Correctional Association offers accreditation to the nation’s correctional facilities, but the program is completely voluntary4. To meet their standards for accreditation, a facility must allow “each offender the opportunity to have at least 20 minutes of dining time for each meal,” and mandates that state meals should not be spaced more than 14 hours apart—about 10 hours longer than common guidance on healthy meal spacing5. Furthermore, all carceral facilities must have a licensed dietician on staff to review menus in order to receive ACA accreditation4. These dieticians, in practice, “are called to figure out ways of achieving states’ minimum calorie counts and vitamin and nutrient intakes via tubs of margarine and fortified mineral powders and supplements6.” However, other regulations have been made policy through lawsuits filed by prisoners who feel their human rights have been violated by the food fed to them during their incarceration.

Countless lawsuits have been filed against correctional facilities—yet time and time again, courts uphold the policies that are causing myriad mental and physical trauma and health complications. The primary governing law for prison food is the Eighth Amendment—namely that correctional facilities must not deprive prisoners of the “basic necessities of life,” in order to align with the prohibition of cruel and unusual punishment of convicted prisoners7. Furthermore, Rhodes v. Chapman, 452 U.S. 337 (1981) established that the administration of carceral facilities must be compatible with the evolving standards of decency that mark the progress of a maturing society8.” Nevertheless, Gardner v. Beale, 780 F.Supp. 1073 (E.D.Va. 1991), upheld that a “two meal policy” in prisons was not in violation of the 8th Amendment after a prisoner complained of only being fed in 18-hour increments, because only “mental damages” were suffered9. Furthermore, in 1995, the Supreme Court ruled that “prison regulations do not give prisoners an affirmative right under the Constitution,” and prisons may no longer sue for the enforcement of prison policy10.

The Bureau of Prisons’ Food Service Manual (FSM), which governs policy at federal prisons, states that “Inmates will be provided with nutritionally adequate meals, prepared and served in a manner that meets established Government health and safety codes,” but nowhere in the FSM do they expand upon what nutritionally adequate entails11. There are also specifications for Daily Recommended Intake—including a caloric recommendation of 2,816 calories per day—but no requirements to follow them or to provide this information in an accessible way to the incarcerated11.

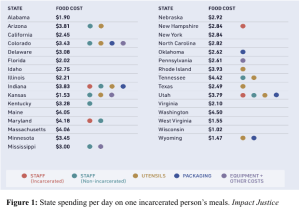

Notably, there exists no nationwide mandate for state and local prisons on the cost of a meal, or on the minimum amount of calories or nutrients they must contain. States must comply with their own standards, but there is no guarantee that these standards are in line with well-studied dietary recommendations. The United States Department of Agriculture releases an official “Thrifty Food Plan” yearly, outlining the average cost to feed a United States citizen “a nutritious, practical, and cost-effective diet” based on Dietary Reference Intakes and the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-202512. This year, the weekly cost to feed a 20-50 year old male (also the age and sex of the average incarcerated American) was $69.30, or about $10 a day. In 2020, the Oklahoma Department of Corrections spent $2.26 a day to feed a “prisoner”13. Other states’ reported amount spent per incarcerated person is shown in Figure 1.

The USDA, the nation’s premier source for information on food safety and optimal nutrition, determined that approximately $10 a day is needed to adequately feed and nourish a 30-year-old man, yet this same health guideline is not extended into the carceral system. This trend does not stop with the economics of prison food—a myriad of other commonly accepted and well-established federal guidelines on nutrition are abhorrently ignored and violated within the carceral system, as there exists no law mandating that prisons and jails must follow the same guidelines that govern how every other population in the United States eats.

The USDA’s Dietary Guidelines for Americans and the Dietary Reference Intakes, issued by the National Academy of Sciences, are synthesized into MyPlate, the widely-publicized guidelines for the American diet. MyPlate emphasizes “vegetables, fruits, whole grains, seafood, eggs, beans and peas, nuts and seeds, and some dairy and meat products—prepared with little or no added solid fats, sugars, refined starches, and sodium.14” In contrast to these national guidelines, in a month-long study of Georgia prisons, the average cholesterol intake was 156 percent the recommended amount, sodium was 303 percent the recommended amount, and total calories for female inmates were 121 percent the daily recommended amount15.

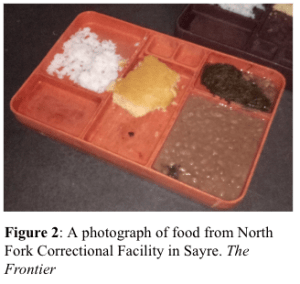

It is impossible to overstate the dehumanizing, humiliating, and disgusting nature of prison food. Meals served in “chow halls” have been compared to “food intended for livestock” by some formerly incarcerated people16. A breakfast served in an Alabama jail included one scoop of unsweetened grits, one slice of bread, and less than half of an egg17. Three quarters of formerly incarcerated national survey respondents said they were served spoiled or rotten food while in prison18. Some of the incarcerated are starving—94 percent of formerly incarcerated people surveyed by Impact Justice said they could not eat enough to feel full—whereas others are exhibiting trauma-induced eating behaviors that cause rapid weight gain like binging and hoarding18. Aside from tasting like “a ground-up gym mat” and being so scarce that some prisoners resort to licking syrup packets, the food in prisons and jails models a diet that is a one-way ticket to chronic disease 19,17.

It would be an understatement to simply say that studies have shown that nutrition is linked to better health outcomes. Almost half of deaths in the US due to cardiometabolic diseases (heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes, hyperlipidemia, or hypertension) can be directly linked to suboptimal nutrition20. Decreasing the amount of sodium, increasing omega-3-fats and nuts/seeds, limiting processed and red meats, and reducing sugary beverages are all associated with positive health benefits like lower risk of coronary heart disease, type 2 diabetes, cancer, obesity, aggression, and ADHD21-25. Almost one in three prisoners have hypertension, 7.2 percent have diabetes (almost double the rate in the general population), 10 percent have heart problems (10 times the rate in the general population), 25 percent have diagnosed ADHD (five times that of the general population), and one in four prisoners are in serious psychological distress—all diseases that are significantly and consistently associated with poor nutrition26-28. Thus, the lack of adequate economic and legal policies enforcing the proper nutrition and nourishment of the incarcerated is creating an epidemic of physical and mental illnesses for those inside.

The mere experience of incarceration leaves an indelible imprint on the health of an individual. The average time spent in a prison is 29 months according to a 2016 Prison Policy Initiative study—ample time for daily consumption of nutrient-poor, high-calorie diets to leave lasting impacts on cholesterol levels and body fat, as it takes only four weeks for diet to impact these metrics long term29-30 Thus, the health impacts of diet sustained within the walls of the carceral system are carried back into communities, where they impose a financial burden on already stretched-thin local, urban health systems.

Furthermore, the legal policies governing food access for the formerly incarcerated compound upon the atrocious policies within the system to create cycles of chronic disease that directly intersect with cycles of incarceration hyper-prevalent in Black and Brown communities. The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, formerly food stamps, has been associated with improved dietary quality and increased food security—along with measurable improvements in children’s health, academic performance, and generally lifting people out of poverty31. However, some states have historically imposed a lifetime ban on SNAP and/or TANF (Temporary Assistance for Needy Families) for those with previous drug felony convictions. Many states have modified this ban (though South Carolina maintains a total ban on SNAP) by allowing more individuals to regain access to these public assistance programs with completion of their sentence or concurrent fulfillment of a probation sentence32. Currently seven states maintain complete bans on TANF access for those formerly incarcerated for drug charges32.

Public assistance programs like SNAP and TANF are essential to those who were formerly incarcerated, and their families. The main benefit of these public assistance programs pertains to accessing low-cost meals, of essential importance to the 91 percent of those released from carceral facilities who experience food insecurity33. Furthermore, with over 35.5 million children with a formerly incarcerated parent, the denial of a family’s access to SNAP or TANF, among other public assistance programs, negatively impacts the health of the child, which contributes to the perpetuation of health disparities in communities disproportionately impacted by hyperincarceration34.

The structural and systemic racism embedded into the United States carceral system, evident through the demographics of hyperincarceration, has created communities that are facing higher rates of chronic disease and food insecurity spawning from their time spent behind bars. The lack of coherent, cohesive laws on food quality and quantity, including a lack of enforcement of federal guidelines at a state and local level, allow for unappetizing, unsatisfying, unhealthy, and inhumane portions of food to be served day in and day out to those in prisons and jails. The mental and physical health impacts of this poor diet create hyper prevalence of cardiometabolic disease—and these problems are only intensified as the formerly incarcerated are denied access to public assistance and live in areas designated as “food deserts” where food insecurity is the norm. It becomes highly evident when examining the relationship between incarceration and food that the incarcerated are treated as second-class citizens in the United States in a way that is impermissible and contributes to lasting health disparities both inside and outside of the pejorative walls of a carceral facility.

References:

- Maruschak LM, Berzofsky M, & Unangst J. Medical problems of state and federal prisoners and jail inmates, 2011-12. US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics. 2015 Report No. NCJ 248491. 1-23

- Freudenberg N. Adverse effects of US jail and prison policies on the health and well-being of women of color. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(12):1895-1899. doi:10.2105/ajph.92.12.1895

- Price JH, Khubchandani J, McKinney M, Braun R. Racial/ethnic disparities in chronic diseases of youths and access to health care in the United States. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:787616. doi:10.1155/2013/787616

- American Correctional Association. 2016 Standards Supplement. Alexandria, VA: Commission on Accreditation for Corrections; 2016.

- The Best Times to Eat. Northwestern Medicine Nutrition. https://www.nm.org/healthbeat/healthy-tips/nutrition/best-times-to-eat Accessed December 23, 2022.

- Neate R. Prison food politics: the economics of an industry feeding 2.2 million. The Guardian. 30 Sep 2016: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/sep/30/prison-food-spending-budget-cuts-minnesota. Accessed December 23, 2022.

- Farber JL. Prisoner Diet Legal Issues. AELE Mo. L. J. 2007; 7: 301-311. ISSN 1935-0007

- Rhodes v. Chapman, 452 U.S. 337, 101 S. Ct. 2392, 69 L. Ed. 2d 59 (1981).

- Gardner v. Beale, 780 F. Supp. 1073 (E.D. Va. 1991).

- Sandin v. Conner, 515 U.S. 472, 115 S. Ct. 2293, 132 L. Ed. 2d 418 (1995).

- US Federal Bureau of Prisons. Food Service Manual. 2011. P470006. Available at: http://www.acfsa.org/documents/stateRegulations/Fed_Food_Manual_PS_4700-006.pdf. Accessed March 1, 2016.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service . Thrifty Food Plan, 2021. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service; Washington, DC, USA: 2021. p. 125.

- Bailey B. Oklahoma spends less than a dollar a meal feeding prisoners. The Frontier. Published October 20, 2020. Accessed December 23, 2022. https://www.readfrontier.org/stories/oklahoma-spends-less-than-a-dollar-a-meal-feeding-prisoners/

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services & U.S. Department of Agriculture. (2015). Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2015-2020. 8th Edition

- Cook EA, Lee YM, White BD, Gropper SS. The Diet of Inmates: An Analysis of a 28-Day Cycle Menu Used in a Large County Jail in the State of Georgia. J Correct Health Care. 2015;21(4):390-399. doi:10.1177/1078345815600160

- Nargi L. Poor food in prison and jails can cause or worsen eating and health problems. and the effects can linger long after release. The Counter. https://thecounter.org/poor-food-prison-jail-causes-health-problems-trauma/ Published February 2, 2022. Accessed February 23, 2023.

- Santo A, Iaboni L. What’s in a prison meal? The Marshall Project. https://www.themarshallproject.org/2015/07/07/what-s-in-a-prison-meal Published July 7, 2015. Accessed February 23, 2023.

- Soble L, Stroud K, Weinstein M. Eating Behind Bars: Ending the Hidden Punishment of Food in Prison. Impact Justice. 2020. impactjustice.org/impact/food-in-prison/#report

- Brown PL. The ‘Hidden Punishment’ Of Prison Food. New York Times, March. 2021;2.

- Micha R, Peñalvo JL, Cudhea F, Imamura F, Rehm CD, Mozaffarian D. Association Between Dietary Factors and Mortality From Heart Disease, Stroke, and Type 2 Diabetes in the United States. JAMA. 2017;317(9):912-924. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.0947

- Farquhar WB, Edwards DG, Jurkovitz CT, Weintraub WS. Dietary sodium and health: more than just blood pressure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65(10):1042-1050. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2014.12.039

- Meyer BJ, Byrne MK, Collier C, et al. Baseline omega-3 index correlates with aggressive and attention deficit disorder behaviours in adult prisoners [published correction appears in PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0129984] [published correction appears in PLoS One. 2018 May 7;13(5):e0197231]. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0120220. Published 2015 Mar 20. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0120220

- Ros E. Health benefits of nut consumption. Nutrients. 2010;2(7):652-682. doi:10.3390/nu2070652

- Qian F, Riddle MC, Wylie-Rosett J, Hu FB. Red and Processed Meats and Health Risks: How Strong Is the Evidence?. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(2):265-271. doi:10.2337/dci19-0063

- Malik VS, Hu FB. The role of sugar-sweetened beverages in the global epidemics of obesity and chronic diseases. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2022;18(4):205-218. doi:10.1038/s41574-021-00627-6

- Maruschak LM, Berzofsky M, Unangst J.. Medical problems of state and federal prisoners and jail inmates, 2011-12 US Dept of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics. 2015: 1-22

- Tully J. Management of ADHD in Prisoners-Evidence Gaps and Reasons for Caution. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:771525. Published 2022 Mar 18. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2022.771525

- Bronson J, Berzofsky M. Indicators of mental health problems reported by prisoners and jail inmates, 2011–12. Bureau of Justice Statistics, (Special Issue), 2017: 1-16.

- Prison Policy Initiative. Counting Incarcerated People At Home in the Census. 2016. 1-18

- Ernersson A, Nystrom FH, Lindström T. Long-term increase of fat mass after a four week intervention with fast food based hyper-alimentation and limitation of physical activity. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2010;7:68. Published 2010 Aug 25. doi:10.1186/1743-7075-7-68

- Thompson D, Burnside A. No More Double Punishments Lifting the Ban on SNAP and TANF for People with Prior Felony Drug Convictions. CLASP. 2019 https://www. clasp. org/sites/default/files/publications/2019/04/2019.03, 15.

- SNAP Supports Health and Boosts the Economy. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. 2021.

- Wang EA, Zhu GA, Evans L, Carroll-Scott A, Desai R, Fiellin LE. A pilot study examining food insecurity and HIV risk behaviors among individuals recently released from prison. AIDS Educ Prev. 2013;25(2):112-123. doi:10.1521/aeap.2013.25.2.112

- Vallas R, Boteach M, West R, Odum, J. Removing barriers to opportunity for parents with criminal records and their children: A two-generation approach. Center for American Progress. 2015