By Deeya Prakash

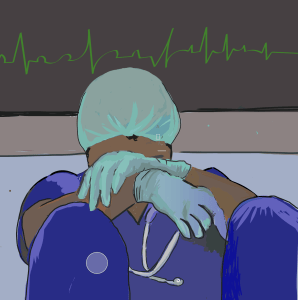

Illustration by Mena Kassa

Silence envelops Dr. Michael Ivy’s cozy office.¹ He has neatly folded the sleeves of his striped button-down and adjusts them as he moves to fiddle with his bright orange tie. Behind him, a bookcase overflows with books and memorabilia; framed photographs squeeze into the gaps. Ivy pauses for several moments before inhaling sharply. “At some point,” he says, “you have this thought, ‘It wouldn’t be so bad if I died.’”

The doctor fiddles again with his tie and looks away before he speaks again. “I’d seen a lot of people die. I was a trauma surgeon. So it wasn’t hard to figure out a way,” he says. Eventually, his mindset evolved to a chilling assessment: “This isn’t going to end until I die.”

Ivy, deputy chief medical officer at Yale New Haven Health, says his personal experience with physician suicide is “unfortunately all too common.” According to the American College of Emergency Physicians, roughly 300 to 400 physicians die by suicide each year in the U.S., and more than half of physicians know a colleague who has considered, attempted, or died by suicide.2

This rate has been on a steady rise and has skyrocketed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. An increasing number of physicians and medical students report feeling stressed, burned out, depressed, or suicidal. At the end of 2021, the American Medical Association (AMA) reported that nearly 63 percent of healthcare professionals reported symptoms of burnout and depression,3 and the American Association of Medical Colleges found that almost 30 percent of medical students and residents suffer from depression, with 10 percent saying they have suicidal thoughts.4 These statistics beg the question: how come those who prioritize helping others are finding it difficult to help themselves?

The cultural dilemma

The answer to this question can be summed up in one word: culture. The American Psychiatric Association states that medical professionals will often forgo treatment or even acknowledgment of their own mental health or suicidal ideation due to “the medical subculture,” which encourages denial and self-reliance and are at least partly learned implicitly during training.5 Ivy fondly remembers his mentor Dr. John Hansbrough, director of the University of California San Diego Burn Center and a “phenomenal physician.” After Hansbrough’s death, Ivy spoke to Hansbrough’s wife about the medical community’s attitudes towards mental illness, especially the culture surrounding receiving care. “My husband didn’t die from suicide,” Ivy remembers her saying. “My husband died from untreated chronic depression—and the culture the medical community refuses to acknowledge exists.’”

The medical culture stigmatizes mental illness, advocates say, and hampers the willingness to seek care when it is most needed. The AMA reported that 79 percent of physicians agree that there is a stigma surrounding seeking help,6 and about eight out of 10 medical students and residents believe there is a stigma surrounding mental health care, according to a report by Healio, a medical news reporting site.7

Dr. Lauren Allister knows this cultural stigma well.8 An associate professor of emergency medicine at Brown University’s Warren Alpert Medical School, Allister has encountered—and says she empathizes with—the pre-physician/physician attitude of “‘I can do everything.” Physicians are encouraged, she says, to think, “‘I’m perfect at everything. I can handle everything. Getting help is weak.’”

Ivy echoes this sentiment. Had he shared his experience of depression during his medical training, he says, “Somebody probably would have told me ‘You shouldn’t be a surgeon.’”

In response to this culture, certain healthcare administrations have created leadership positions dedicated to addressing the epidemic of mental illness and the stigma around it. Administrators across medical schools and hospitals have taken on positions such as Chief Wellness Officer and Director of Wellbeing, with the goal of reducing stigma, implementing change, and changing professional and educational cultures. As they enforce strategies to address the growing physician suicide rate, it is important to understand their approach’s efficacy; through this paper, several solutions are examined and explored in the hopes that they can provide insight into future endeavors.

An individual, opt-out approach

To begin, several different institutions have adopted the “opt-out approach” to mental health checks. A study published in Mayo Clinic Proceedings took a longitudinal look at 10 primary care clinics across the country, focusing on wellness check-ins with physicians.9 Of the cohorts analyzed, one showed markedly lower levels of employee emotional exhaustion and burnout. The secret to this group’s wellness, the study found, was something none of the other cohorts had established: leader-employee check-ins in which leaders listen, acknowledge, and address work stressors.

Dr. Kelly Holder, chief wellness officer of the Warren Alpert Medical School, specializes in this individualistic approach.10 Within the four walls of her bright office, Holder offers medical students one-on-one attention within their first few weeks of training. Dubbed “wellness checks,” these meetings are mandatory, although students can opt-out. At the sessions, Holder checks in with first-year students and provides them with a “friendly face” to whom they can later turn as needed.

The appointment shows up automatically on every student’s calendar. Later, meeting with Holder, many of them comment that they don’t remember scheduling it, Holder says. They sit at the small round table in her brightly lit office, feet resting on its dandelion-yellow rug. “I put the session on their schedule,” Holder says. “They’re not required to attend, but they have to cancel if they don’t want to.”

Holder asks students a few questions about how they’re adjusting to medical school. She provides each student with resources and assures them that she is a resource as well. Meetings range, she says, from general discussions to deep conversations, depending on the student’s engagement and background.

Holder says that she has received positive feedback from first-year students regarding the wellness checks, reporting that they probably wouldn’t have made an appointment and are glad they had the meeting.

Other institutions, from hospitals to medical schools, have also implemented opt-out wellness meetings. Initial research has supported the method’s effectiveness. In a study done by the Journal of Graduate Medical Education, researchers analyzed the efficacy of an opt-out wellness check-in within an internal medicine residency cohort.11 They found that 93% of physicians attended their meeting, and those who attended reported high “convenience” and low “embarrassment.”11 Opt-out appointments minimize the discomfort that physicians face when scheduling their appointments. The study also found that physicians were likely to return for future visits if they had concerns about depression, anxiety, and burnout.

A match-based approach to finding support

Just a few miles from Holder’s office lies another approach, one championed by Dr. Lauren Allister. Associate professor of emergency medicine, Allister is also the Director of Wellness for the emergency medicine department, a new position created by Brown which she filled a few years ago. According to the AMA, 38 percent of hospitals have established well-being committees, with 10 percent assigning “chief wellness officers” or similar positions.12

Still, Allister believes that committees and wellness officers are not enough. The root of the crisis, she says, lies in the sheer number of steps clinicians need to take to seek help. Allister experienced this process herself when she was going through medical school. She places a hand over her face as she remembers her mental health challenges, and the hoops she had to jump through: For anyone at her school to meet with a mental health provider, they first had to find a primary care physician who would provide a referral. “You can do the legwork yourself” to find a doctor, she says, but many find that the doctor doesn’t accept your insurance. Often, healthcare professionals “have to keep looking until they find someone who does,” Allister says, “or find a provider to pay out of pocket, which is incredibly expensive.”

In a survey by the National Alliance on Mental Illness, 55 percent of respondents who had looked for a new mental health provider in the last year contacted psychiatrists who were not accepting new patients.13 Fifty-six percent found providers, but those clinicians didn’t accept their insurance. And, 33 percent reported difficulty finding any mental health provider who would accept their insurance, either in- or out-of-network. Along with long hours, heavy caseloads, and a high level of burnout, many physicians have difficulty navigating the very care system they work in. This is a massive deterrent to finding help.

Even when it proves semi-successful, Allister says, “You have to call a number, speak to someone. Call another number. Stay on hold. Transfer. Call another number. It’s just many, many steps,” Allister says, sighing. “I think the administrative burden of that, even in a well person, is probably prohibitive.” This is why Allister formed Physicians Helping Physicians, a one-step care-match program for physicians in her department. With her program, emergency medicine physicians at Warren Alpert Medical School who require mental health support can simply call one of two psychiatrists designated to the staff, explain their reason for calling, and indicate their insurance plan. Within 24 to 48 hours, a psychiatrist will match them with a provider in their area, whom they can call to set up an appointment.

Allister expanded the program at residency orientation for Emergency Medicine physicians, and she saw a “huge uptick in signups.” Proud of its impact, Allister says that she has received nothing but positive feedback from the more than 10 percent of physicians and residents who have taken advantage of the program.

NAMI emphasizes the importance of programs like this, writing on its website that people’s difficulties finding a provider, “may lead to them seeking less care—or going without any care at all.” Allister continues to expand and publicize her efforts. She hopes that her program will become “the norm” nationally.“Physicians shouldn’t have to go through all that just to see someone. It should be easy, and I hope to make it easy,” she says.

A system-based approach to reducing stress

Others in wellness leadership place more emphasis on the system. To promote wellness for his network, Dr. Jonathan Ripp, senior associate dean for well-being and resilience and chief wellness officer at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, works to assess specific stressors of the physician experience.14 Such priorities encompass technology and electronic records, two facets of the physician process that “prove increasingly frustrating” according to Ripp.

As per the Journal of Community and Public Health, electronic health records are a significant source of burnout.15 As medicine has relied more and more on technology, “technoburnout” has increased. Physicians struggle with how much time they spend at a computer entering information and ordering medication, rather than seeing and interacting with patients.

Though electronic records have improved physician administrative duties, such as simplifying the scheduling of patient appointments and providing remote access to patients’ charts, these duties have consumed the profession, with physicians often spending extra time outside of work entering notes and orders.16 U.S. physicians who use electronic health records spend an average of 1.84 hours a day completing documentation outside work hours, according to research published in the Journal of American Medical Association (JAMA) Internal Medicine.17 The researchers found that long work days turn into consuming professions, cutting into personal time and increasing levels of burnout.

Ripp focuses on the stress of electronic records-keeping as a way to reduce physician burnout, thereby improving mental health.“A lot of the specific areas that we focus on, when it comes to efficiency, have to do with technology,” he says. He hopes to improve physicians’ “interactions with the electronic healthcare record and the ordering systems. So we spend a lot of time trying to influence how those technologies are used, so that the electronic health record works for the healthcare worker, and not the other way around,” Ripp says.

But Ripp also says that technology as a cause of stress is just one factor he wants to address. Solving the medical community’s mental health crisis, he says, “is about creating a community and system where people feel valued.” Modifying and improving the medical records system is just one area for reform, and he is hoping to utilize physician feedback to explore more opportunities for growth. Improving the system in which clinicians work can help them, Ripp says, to “derive meaning and fulfillment from their profession.”

Focusing on the system, Ripp argues, encourages individuals to value others and their well-being. “We create a space where physicians can efficiently and effectively do their work, and at the end of the day, they have the resources to do what they’re trained to do.”

An advocacy approach

Dr. Ivy adjusts in his seat as he prepares himself to reply to a question. “I’m happy to talk about my experience,” he says, but warns that it “gets a little gloomy.”

Ivy’s personal experience with suicide came in 2002 when he was serving as chief of trauma at Bridgeport Hospital, juggling an abrupt increase in administrative work, taking on “six trauma cases a week” and experiencing “intense troubles at home.” He was shouldering too much work, and recalls feeling “incredibly burned out.”

He was tired and irritable, he says. “I’m not normally irritable.” He found himself becoming “very cynical. I started blaming myself for the things that weren’t going well,” and he felt like he was “letting everyone down.” These factors, plus missing important family events and suffering other health problems, were “all it took.”

After reaching out to a supervisor and spending months in therapy, Ivy remembers feeling better, but not back to normal. What really helped him turned out to be helpful for others: advocacy. “I think the language needs to change from ‘if you need help, seek these resources’ to ‘when I needed help, this is what I did.’”

Ivy shares his story whenever he can, whether it’s with his residents during rounds or at large college panels. Each time he tells his story, he believes, is a step towards a solution. Sharing mental health struggles with other physicians, he hopes to eradicate the stigma, to normalize seeking help.

Ivy says he’s received many “heartbreaking and relatable” emails in response to his personal struggle with mental health in his position. He says he’s had many conversations with people who have been moved by what he has to share. He talks with two types of people: those who have never experienced depression and need to hear what it’s like, and those who have and need to hear that they are not alone.

“I try to help physicians understand what it can be like for a person who’s depressed and why they might want to end their life. But also, more importantly, I’m talking with people who are struggling and trying to help them feel not alone, give them the sense that it can be okay. And that it’s okay to get help,” he says.

“I think in my ideal world, people would understand they should treat mental health illness or struggles like you would asthma. You gotta go get seen. You can’t treat it yourself. That’s the bottom line.”

In the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Mayo Clinic writes that physician burnout jumped nearly 65 percent, with many instances manifesting as depression, anxiety, and suicidal thoughts.18 In the aftermath, medical institutions are combating the issue in their own ways. Allister and others say that, ultimately, the problem is cultural. There is no catch-all solution. It will also likely be years before efforts to address the problem can be assessed. Allister and others believe that, ultimately, solutions lie in changing the culture of medicine. “I am just happy that I get to help move the cultural needle,” she says.

References

- Ivy, Michael. 16 October, 2023.

- Physician Suicide. Home Page. www.acep.org/life-as-a-physician/w ellness/wellness/wellness-week-articles/physician-suicide.

- Measuring and Addressing Physician Burnout. American Medical Association. 3 May 2023. www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/physician-health/measuring-and-addressing-physician-burnout#:~:text=At%20the%20end%20of%202021,address%20the%20physician%20burnout%20crisis.

- Paturel, A. Healing the very youngest healers. American Association of Medical Colleges. 21 January, 2020. https://www.aamc.org/news/healing-very-youngest-healers.

- Yellowlees, P. et al. Preventing Physician Suicide Requires Changing Culture of Medicine. Psychiatric News. 28 Feb. 2019, psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/full/10.1176/appi.pn.2019.3a34.

- Preventing Physician Suicide. American Medical Association. 3 Oct. 2023. www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/physician-health/preventing-physician-suicide.

- Person, et al. “‘If You Seek Help, You Risk Your Career’: Physician Suicide Needs Solutions, Not Silence.” Healio. 21 Sept. 2023, www.healio.com/news/primary-care/20230921/if-you-seek-help-you-risk-your-career-physician-suicide-needs-solutions-not-silence.

- Allister, Lauren. 11 October, 2023.

- Hurtado D. A. ScD a d, et al. Promise and Perils of Leader-Employee Check-Ins in Reducing Emotional Exhaustion in Primary Care Clinics: Quasi-Experimental and Qualitative Evidence. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 4 Apr. 2023, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S002561962200708X?casa_token=b_Lk2bQjzrkAAAAA%3Aoqb_p5ROsRzk8KJ9Uty-RBQtYuL-HuX9hQi3sEJ6Jm03WKhhCh91lWexb7Tb0A1edD2BZ03T6n4.

- Holder, Kelly. 26 September, 2023.

- Hjelvik, A. et al. A Peer-to-Peer Suicide Prevention Workshop for Medical Students. MedEdPORTAL : The Journal of Teaching and Learning Resources, U.S. National Library of Medicine. 19 Apr. 2022. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9016109/.

- Robeznieks A. Doctor shortages are here-and they’ll get worse if we don’t act fast. American Medical Association. April 13, 2022. https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/sustainability/doctor-shortages-are-here-and-they-ll-get-worse-if-we-don-t-act.

- The Doctor Is Out. NAMI, www.nami.org/Support-Education/Publications-Reports/Public-Policy-Reports/The-Doctor-is-Out.

- Ripp, Jonathan. 28 November, 2023.

- Budd J. Burnout related to electronic health record use in Primary Care. Journal of primary care & community health. 2023. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10134123/#:~:text=Electronic%20Health%20Records%20(EHRs)%20are,%2C%20COVID%2D19%20pandemic%20stressors.&text=Figure%201.,of%20burnout%20among%20U.S.%20physicians.

- Manca, D. Do Electronic Medical Records Improve Quality of Care? Yes. Canadian Family Physician Medecin de Famille Canadien, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Oct. 2015. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4607324/#:~:text=Electronic%20medical%20records%20have%20been,remote%20access%20to%20patients’%20charts.

- Gaffney, A. Medical Documentation Burden among Us Office-Based Physicians. JAMA Internal Medicine. JAMA Network. 1 May 2022, jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/2790396#:~:text=Physicians%20participating%20in%20VBP%20spent,outside%20office%20hours%20in%202019.

- Kalmoe, M. et al. Physician Suicide: A Call to Action. Missouri Medicine, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 2019. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6690303/.