Authors: Gauri Gadkari | Kento Suzuki | Riki Fameli | Rinchen Dolma | Youkie Shiozawa

ABSTRACT

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, we have witnessed enormous disparities in the severity of its global impact. A significant factor that may influence the outcome of the disease is access to sufficient health care. The main objective of this study is to determine the effects of universal health coverage (UHC) status on COVID-19 outcomes within a given country. A mixed methods approach of quantitative and qualitative analysis was used. The four quantitative outcomes explored were: cumulative case counts per 100,000; case fatality rates; testing per 1,000; and recovery rates. A total of 29 countries worldwide were investigated, including 17 UHC countries and 12 non-UHC countries. For each country, data on all six outcomes, as well as qualitative data regarding specific health policies, were recorded to examine the effects of a country’s UHC status on the outcomes of the pandemic in the population. Our preliminary analysis shows that UHC status may not protect against mortality in a pandemic, as countries with a case fatality rate (CFR) greater than 5% were countries with UHC. We noticed, however, that many Asian countries with UHC reported lower CFRs than their European counterparts. Additionally, our study shows that UHC countries had higher recovery rates than non-UHC nations. As the pandemic continues, follow-up analyses must be conducted in the near future to analyze the effects of UHC and access to healthcare.

BACKGROUND

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an infectious respiratory disease caused by the virus called severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), belonging to the coronavirus family. COVID-19 has spread across the globe soon after the index case was observed in Wuhan, China in late 2019, and there have been approximately 268 million cases worldwide as of December 10, 2021.1 The impact that COVID-19 is causing in different parts of the world is disparate, and it is needless to say that access to healthcare plays a crucial role in determining the severity of the spread of infectious diseases. One of the many measures to assess healthcare access is Universal Health Coverage (UHC) status. WHO defines UHC as follows: “Universal health coverage (UHC) means that all people and communities can use the promotive, preventive, curative, rehabilitative and palliative health services they need, of sufficient quality to be effective, while also ensuring that the use of these services does not expose the user to financial hardship.”2 UHC is a central target of the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), and is considered a critical component of sustainable development and poverty reduction, as well as a key element to reducing social inequities.3 Given the recent rise in demand for UHC across the globe, it is worthy to probe the extent to which it plays a role in mitigating deleterious outcomes from the pandemic.

However, research or data that compare the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic between countries by UHC status are very scarce. We identified one observational study that looked at the relationship between countries’ UHC status and the impact of COVID-19.4 The study focused solely on one outcome, the case fatality rates, and concluded that UHC status is not associated with the COVID-19 mortality rates.4 Moreover, the researchers categorized countries into simply UHC or non-UHC countries, which dismisses the sheer diversity in the ways in which healthcare systems are structured in each country and the degree to which UHC is achieved among the traditionally UHC-categorized countries. The main objective of this study is to determine the effects of UHC status on the outcomes of COVID-19. The six outcomes explored are the following: cumulative case counts per 100,000, case fatality rates, cumulative testing, testing per 1,000, hospital beds per 1,000, and recovery rates. In total, thirty countries worldwide are investigated, including seventeen UHC countries, and thirteen non-UHC adopting countries. For each country, data on all six outcomes are recorded to examine the relationship between the UHC status of the country and its public health policies, as well as the effects of the pandemic on the population.

METHODS

We used a mixed methods approach to understand the differences between countries’ response to the COVID-19 virus. Public data, such as case counts and recovery rates, were used to make quantitative comparisons between countries. The reasons for differences in COVID-19 response between countries is multifold, with each country’s social and economic background influencing the type and effectiveness of steps taken. We took a qualitative approach to understanding the profile of each country’s COVID-19 response to account for this complexity. We began with a list of countries that were epicenters of the epidemic early in the year, such as China, Italy, France, and South Korea. This resulted in many European countries being included. After this, we chose countries that were of interest to the team members. Countries from across 6 continents were chosen, which captures the global ramification of this pandemic. Universal healthcare (UHC) refers to a system in which quality healthcare is provided by the federal government to all citizens regardless of their ability to pay. Countries without this healthcare provision are identified as non-UHC in this paper. Countries from all six continents were chosen, with 17 countries with Universal Health Care (UHC) and 13 countries without (non-UHC).

The quantitative approach: The quantitative data consisted of key measures that were globally used to track the status of the pandemic. These key measures were case counts per 100,000 persons, case fatality rate (CFR), recovery rate, COVID-19 testing per 1,000 persons and general hospital beds per 1,000 persons. The sources of these data varied from national to intergovernmental COVID data tracking systems. For the purpose of being in the same time frame across measures that were changing daily, quantitative data collection began in May and ended on July 18th, 2020 to make the values comparable. Simple descriptive analysis was utilized to compare countries across these measures to get a preliminary understanding of COVID responses. Microsoft Excel was utilized to clean the data and produce the statistical graphics.

The qualitative approach: Qualitative content analysis method was utilized to gain an in-depth understanding of the respective countries that were being assessed, and their experiences with the pandemic. This method can thereby serve as a supportive analytical role in combination with the aforementioned quantitative data. The content search was conducted in the months of May – July 2020, using Google engines and databases (Google Scholar, PubMed) with the search terms: ‘‘COVID-19” and the name of the individual countries. The qualitative data for this project were compiled from newspapers, television, journal articles and social media.

Table 1. List of countries according to their UHC status

| UHC | Non-UHC |

| Belgium | Brazil |

| Cuba | China |

| France | Egypt |

| Germany | India |

| Guatemala | Kenya |

| Indonesia | Lesotho |

| Italy | Nepal |

| Japan | Nigeria |

| New Zealand | Pakistan |

| Russia | Philippines |

| South Korea | South Africa |

| Sri Lanka | US |

| Sweden | Yemen |

| Switzerland | |

| Taiwan | |

| Thailand | |

| UK |

RESULTS

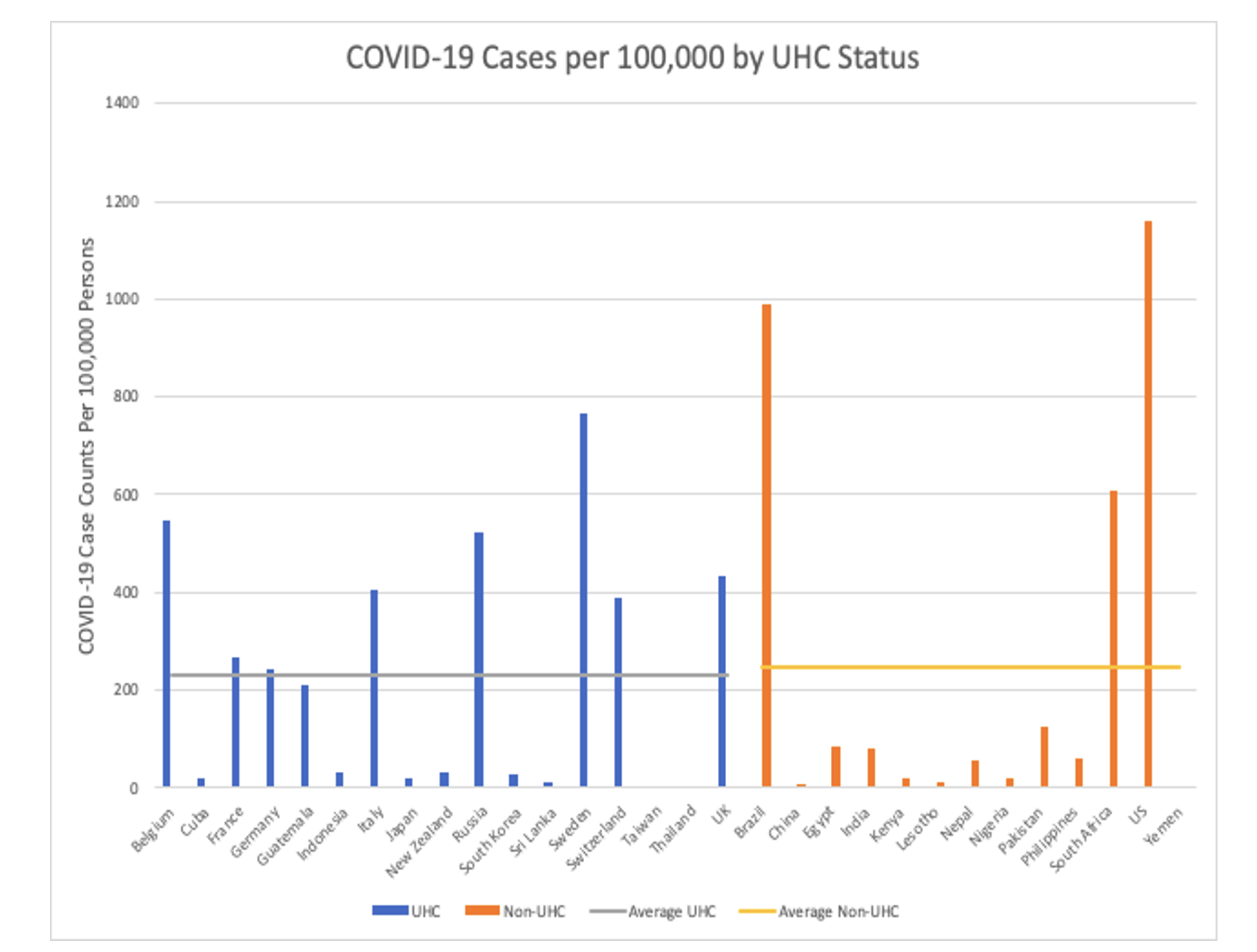

Figure 1. COVID-19 Cumulative Case Counts per 100,000 persons

The U.S. and Brazil — both countries without a UHC system — reported the highest number of cumulative cases per 100,000 persons (Figure 1). The majority of the countries reporting greater than 200 cases per 100,000 persons have a UHC system. In contrast, many of the non-UHC countries reported case counts lower than that. Since recognition of cases is highly dependent on testing capacity and the number of tests conducted by each country, these findings likely reflect potential biases. Some researchers claim that Brazil may have 12 times more cases of the novel coronavirus than are being officially reported by the government.5,12 The country did not possess the manufacturing power to produce the large number of tests needed, and found it difficult to compete with other, wealthier countries in purchasing tests from China. Laboratories were also unequipped to process so many tests. 6

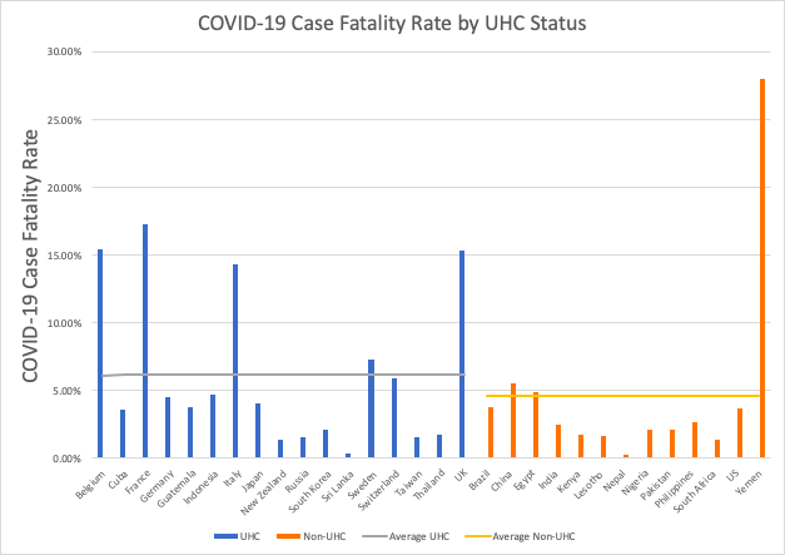

Figure 2. Case Fatality Rates

Yemen reported the highest case fatality rate (CFR) of 28.02%. This can potentially be explained by the humanitarian crises that the country is experiencing due to the ongoing civil war. According to WHO representative Dr. Ahmed Shadoul, Yemen’s healthcare system is close to collapse.7 Around 23% of health facilities are no longer functional, and the country is largely dependent on the limited supplies from international humanitarian organizations7. The second trend observed is that the majority of countries following Yemen with greater than 5% CFR were European countries with a UHC system. More specifically, these countries were Italy, Belgium, UK, and France. Except for Yemen, the majority of the non-UHC countries reported less than 5% CFR. However, there is concern over the validity of the information provided by some of the countries8. For example, researchers argue that there is a vast underestimate of the true death toll from the pandemic in many parts of across Latin America and the Caribbean, with some places over 80% of excess deaths remain unaccounted for.8

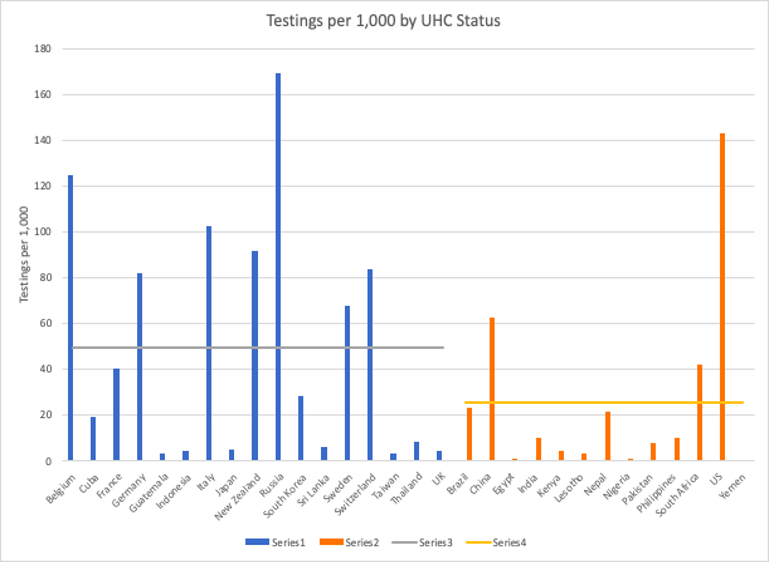

Figure 3. Testing per 1,000 people

Non-UHC countries, with the exception of the US, have lower testing per 1,000. This may be due to a more targeted testing protocol being used in these countries. Surprisingly, some of the UHC countries that have managed COVID well, such as South Korea, Sri Lanka, and Taiwan, have relatively low testing rates. This may have to do with the mindset of the general public in those countries. At the same time, we cannot dismiss the fact that testing rates are related to the financial status of individual countries, as most of the lower-income non-UHC countries explored here, such as Egypt, Guatemala, Lesotho, Kenya, and Nigeria, have very low testing rates (Figure 3).

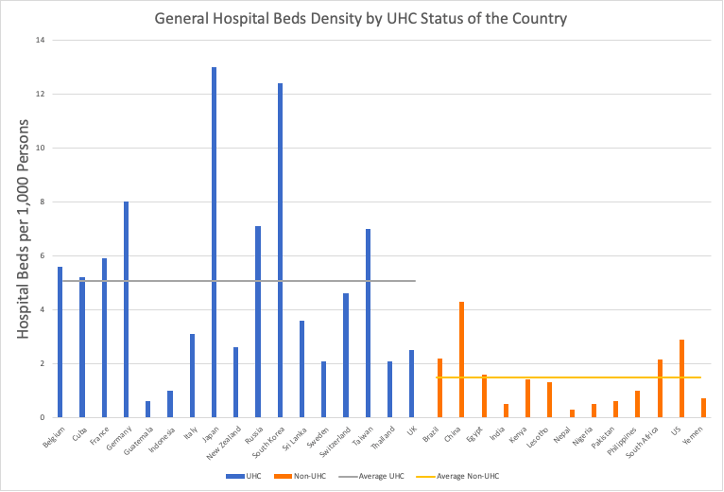

Figure 4. Hospital Beds Per 1,000 Persons by UHC Status of the Country

As per WHO, hospital beds are used to indicate the availability of inpatient services which is a marker of hospital capacity in a respective country. However, there is no global norm for the density of hospital beds in relation to the total population.9 During the peak stages of the pandemic, severe shortages of hospital beds for COVID-19 patients and patients with other medical conditions were reported. The data presented here does not provide information specific to the countries during the pandemic. However, the trend observed here is quite comparable to the reports made by some of the individual countries. For instance, the African nations (Kenya, Lesotho, and South Africa) reported disproportionate shortages of ICU beds for COVID-19 patients.10 Overall, countries reporting 4.5 or more hospital beds per 1,000 persons have a UHC system. All of the countries without a UHC system reported less than 4.5 hospital beds per 1,000 persons (Figure 5).

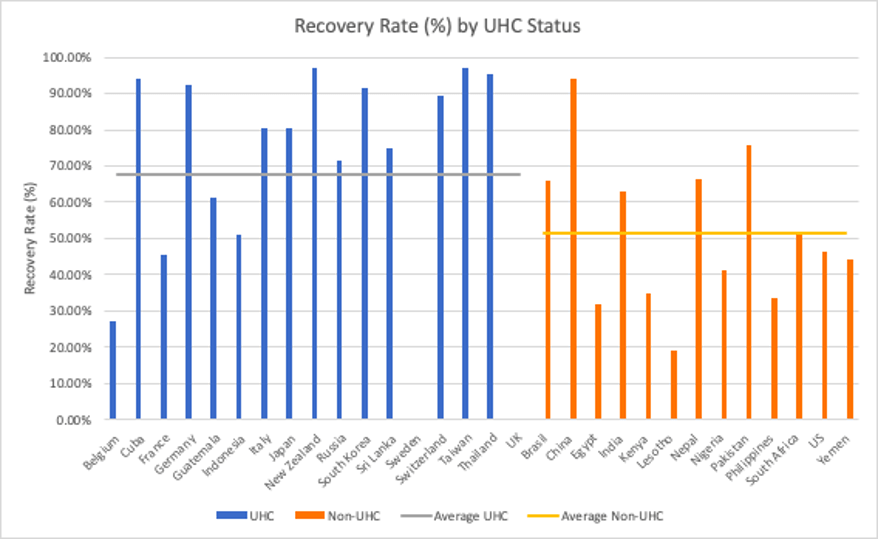

Figure 5. Recovery Rates by UHC Status of the Country

A recovery rate is defined as the rate of transition from the stage of infection with the disease to recovery from disease.11 Figure 6 outlines that there may be an association between the recovery rate of a country and its UHC status. The majority of the UHC countries have recovery rates greater than 70%; that is, ten out of the sixteen UHC countries that were investigated, recorded a recovery rate ranging from 70% to 97.16%. Nonetheless, the recovery rates of the two UHC countries, Sweden, and UK, could not be calculated accurately due to the lack of recorded data on the countries’ recovered cases. Further investigation is necessary in making a conclusion about these two UHC countries. The lowest recovery rate among the UHC countries were Belgium and France with a rate of 27.25% and 45.36%, respectively. The average recovery rate of the UHC countries is 67.59%, and 51.46% for the non-UHC countries. From these points, there is a possible association between the recovery rates of countries with UHC status. Eight of the thirteen non-UHC countries recorded a recovery rate below 50%.

DISCUSSION

UHC is often documented as the prime framework for a national healthcare system. It has been consistently established as a priority target by the WHO Sustainable Development Goals initiative. Evidence from previous studies further corroborates the effectiveness of a UHC system in providing equitable health services at reduced costs. However, our preliminary analysis demonstrated that UHC does not appear to protect against mortality in a pandemic such as with COVID-19. With the exception of Yemen, our findings demonstrate that countries with greater than 5% CFR were countries with a UHC system.

However, there are some discrepancies to further note as Asian countries with UHC reported far lower CFR and were able to contain the virus much more effectively than their European counterparts. This might be explained by the immediate measures taken by Asian countries, which helped with faster containment of the outbreak. Another interesting finding was that countries with UHC had higher recovery rates for COVID-19 than the countries without UHC. This can be potentially explained by the other measures that were included in the analysis such as density of hospital beds and access to testing. In these measures, the majority of the countries with UHC had greater access to such resources. For instance, countries reporting 4.5 or more hospital beds per 1,000 persons have a UHC system. All of the countries without a UHC system reported less than 4.5 hospital beds per 1,000 persons.

Strengths of this study consist of the use of mixed methodologies to provide a broader understanding of the differences in UHC and non-UHC countries’ approach in containing the pandemic. COVID-19 has created complex public health challenges that continue to be influenced by individual countries’ socio-political ideologies. The qualitative data applied in conjunction with the quantitative figures express these complexities and therefore, provides an unbiased perspective. This preliminary study further contributes to the growing scientific literature on COVID-19 and the effectiveness of UHC status in the times of a pandemic.

Although this study looks at thirty nations from six different continents, this size may not be sufficient to make definite conclusions or generalize about associations observed from the data. All of the nations in this study have a population greater than two million, indicating how small countries with a population less than a million were not included in the study. The number of UHC countries and non-UHC countries (17 in comparison to 13) were not equal, making it difficult to compare associations between UHC coverage and the COVID-19 conditions in each country.

Furthermore, this study is a cross-sectional study that focuses on a single point in time. As COVID-19 is still an ongoing pandemic with cases continuing to increase in many places around the globe, this is a major limitation to this study. Although there are many ways to look at healthcare infrastructure, the UHC coverage of the nation was the only variable that was selected. The UHC coverage was also not based on a scale, such as the UHC index, meaning that each country was put into one of two groups: UHC or non-UHC. There are nations where the UHC system is still in the process of developing; these nations were also put in the UHC category, potentially dropping or increasing the averages of the dependent variable, including the testing rates or case counts respectively.

Another limitation to this study is the credibility of the data collected. Some nations may not be reporting their case counts and testing rates accurately, due to political or economic issues. For some nations, the case counts may largely be an underestimate, for example. There may also be biases as some countries may not have a sufficient economic profile to do testing rates, leading to inaccurate data.

For future recommendations, the selection of countries to explore needs to be more holistic with different possibly confounding factors in mind, such as population size, socioeconomic status, and their geographic locations. Most importantly, the number of UHC countries and non-UHC countries need to be equal in future studies. Additionally, future studies can utilize the UHC index as the measure of UHC status. We deliberately did not use the index as we doubted the validity of some of the scores assigned to certain countries; some non-UHC countries had higher scores than UHC countries with robust healthcare access. However, given that the UHC index is the only existent internationally accepted measure of the UHC status and that numerical measures will enable us to quantify the correlation between the UHC status and the COVID-19 impact, it is certainly worth employing the measure in future research. Finally, given that the situation surrounding the spread of COVID-19 alters every single day in different parts of the globe, there is a clear necessity to conduct follow-up analyses similar to this one in the near future.

In conclusion, this preliminary study demonstrated that UHC status may not protect against mortality in a pandemic, as countries with a case fatality rate (CFR) greater than 5% were countries with UHC. However, countries with UHC status had higher recovery rates (67.59%) than non-UHC nations (51.46%) which could be influenced by their access to testing resources and hospital beds. Follow-up analyses must be conducted in the near future to further analyze the effects of UHC and access to healthcare in the times of pandemic, such as the COVID-19.

REFERENCES

1. World Health Organization. (2021). WHO Coronavirus Dashboard. Retrieved December 10, 2021, from https://covid19.who.int/

2. Universal health coverage. (n.d.). Retrieved August 20, 2021, from https://www.who.int/health-topics/universal-health-coverage#tab=tab_1

3. Sustainable Development Goals. (2020, July 2). World Health Organization (WHO). https://www.who.int/health-topics/sustainable-development-goals#tab=tab_2

4. Dongarwar, D., & Salihu, H. M. (2020). COVID-19 Pandemic: Marked Global Disparities in Fatalities According to Geographic Location and Universal Health Care. International journal of MCH and AIDS, 9(2), 213–216. https://doi.org/10.21106/ijma.389

5. Spring, J., & Fonseca, P. (2020, April 13). Brazil likely has 12 times More coronavirus cases than official COUNT, study finds. Retrieved March 06, 2021, from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-brazil-cases/brazil-likely-has-12-times-more-coronavirus-cases-than-official-count-study-finds-idUSKCN21V1X1

6. Mwai, C. (2020, May 15). Coronavirus: Are African countries struggling to Increase testing? Retrieved August 20, 2020, from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-52478344

7. Yemen was facing the world’s worst humanitarian crisis. Then the. (2020, June 3). Science | AAAS. https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020/05/yemen-was-facing-worlds-worst-humanitarian-crisis-then-coronavirus-hit

8. López-Calva, L. F., & R. (2020, July 13). A greater tragedy than we know: Excess mortality rates suggest that COVID-19 death toll is vastly underestimated in LAC. UNDP. https://www.latinamerica.undp.org/content/rblac/en/home/presscenter/director-s-graph-for-thought/a-greater-tragedy-than-we-know–excess-mortality-rates-suggest-t.html

9. Hospital beds (per 10 000 population). (n.d.). Retrieved August 11, 2020, from https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/hospital-beds-(per-10-000-population)

10. Houreld, K., Lewis, D., McNeill, R., & Granados, S. (2020, May 07). Virus exposes gaping holes in Africa’s health systems. Retrieved August 10, 2020, from https://graphics.reuters.com/HEALTH-CORONAVIRUS/AFRICA/yzdpxoqbdvx/

11. Greenhalgh, S., & Day, T. (2017). Time-varying and state-dependent recovery rates in epidemiological models. Infectious Disease Modelling, 2(4), 419–430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idm.2017.09.002

12. Terrence McCoy, H. (2020, April 24). Limits on coronavirus testing in Brazil are hiding the true dimensions of Latin America’s largest outbreak. Retrieved August 20, 2020, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/the_americas/coronavirus-brazil-testing-bolsonaro-cemetery-gravedigger/2020/04/22/fe757ee4-83cc-11ea-878a-86477a724bdb_story.html