By Owen Fahey, Gili Schor, Madeline Day, Kaitlyn Chan, Pran Teelucksingh, Isabel Costas, Angelica Mroczek

Illustration by Ella Olea

Abstract:

Brown University’s campus is composed of approximately 220 structures, some of which date back to 1770. Many of these structures lack the accessibility measures necessary for those living with a disability to thrive. This paper aims to understand Brown University students’ perceptions of accessibility at key locations, how collaboration with administration can improve the accessibility of locations such as the entrance of the School of Public Health (SPH), and raise awareness about campus accessibility. Our ultimate purpose is to ensure that all Brown University students have equal access to education and campus resources. Data was collected via a survey on student experience and opinions surrounding accessibility of campus locations. Student perceptions could be grouped into three overarching themes: 1) Brown is seemingly inaccessible for those utilizing mobility aids, 2) Brown’s accessibility measures are viewed to be minimally sufficient, and 3) Brown’s administration is receptive to improving accessibility measures, but hesitates to prioritize any action. In response, we leveraged our position as students of Brown University’s Public Health Project Committee Executive Board and collaborated with professionals at the SPH in an effort to spearhead an initiative to increase accessibility through the installation of an ADA-compliant automatic door opener. Our survey and event results clearly demonstrated that Brown University’s accessibility measures on campus have room for improvement, considering that many students found the campus to be inaccessible in some aspects. In the future, we hope to investigate additional campus accessibility initiatives to further increase accessibility for all students.

Introduction:

In 1990, the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) was written into law, prohibiting discrimination against individuals with disabilities “in all areas of public life, including jobs, schools, transportation, and all public and private places that are open to the general public.”1 Since its establishment, the ADA has undergone one revision, though research indicates that a lack of accessibility on campuses affects student retention rates. In 2005, the American Institutes for Research found that 46% of students with disabilities who had a high school diploma enrolled in postsecondary education, and 40% of those who enrolled in postsecondary education completed their degrees within 8 years.2 These findings indicate that students with disabilities pursuing postsecondary education still struggle with accessibility-related issues on their campuses. The number of college students with disabilities has also been steadily increasing over time. In 2016, nearly 20% of undergraduate students reported having a disability, and in 2011, 90% of colleges and universities in the United States reported admitting students with disabilities.3,4

Under the ADA, both public and private colleges and universities have the responsibility to provide equal access to education for students with disabilities; however, there is room for interpretation by these institutions. If a college or university can prove that making certain accommodations and modifications “would constitute an undue financial or administrative burden” they can be exempt from making such alterations.5 These exemptions allow institutions to leave certain accessibility accommodations unaddressed, putting students with disabilities at a disadvantage when navigating their postsecondary education.

Given the age and history of many of Brown University’s buildings, the university’s 2022 “Accessibility Handbook & Guidelines” unsurprisingly states that “many of these structures lack accessibility that meet today’s standards.”6 The age of many structures on the university’s campus in conjunction with the topography of Providence’s College Hill neighborhood may present many accessibility challenges for students.

This paper aims to understand the perceptions of Brown University students regarding accessibility accommodations at key campus locations, analyze how collaboration with administration can improve or hinder accessibility improvements to locations such as the entrance to the university’s School of Public Health (SPH), and raise awareness surrounding campus accessibility measures. The SPH’s entrance was selected in particular as our primary structural accessibility goal because the entrance, composed of heavy-set glass doors, was not accessible from the outside and the location is frequented by all students and faculty. Students and faculty reported struggling to handle the doors. To gain an understanding of these concepts, we conducted a short informal qualitative survey through convenience sampling among currently enrolled Brown University students attending school on campus to assess their perceptions of accessibility accommodations. We hope that this project will serve as a foundation to continue improving accessibility for students on Brown University’s campus.

Methodology:

A survey was released to gather insights on public health and disability. The survey consisted of six questions along with one free-response section. The six questions allowed respondents to reflect qualitatively and quantitatively on Brown’s structural environment. To distribute the survey, a QR code was created and shared with students taking public health courses at Brown, posters containing the QR code and project information were displayed at popular campus locations, and students were provided links by various undergraduate concentration departments. Lastly, the survey was sent out to all undergraduate students via university-wide communication through Today@Brown. This approach allowed for a diverse range of perspectives to be collected and a comprehensive understanding of the topic.

A collaboration with members of the PHP 1680I: Pathology to Power class, who held a social awareness event at the entrance of the SPH on December 1st, 2022, allowed us to gauge students’ perceptions of campus accessibility. After receiving prior clearance from the school, they approached all students and faculty passing through the entrance and introduced our shared goal of increasing accessibility at the SPH. Participants then attempted to enter and exit the building’s main entrance using their choice of mobility aid– a wheelchair, a pair of crutches, or a walker. A post-experience survey was administered to participants, who were asked to reflect on difficulties faced during their attempts to enter. Participants were also prompted to consider how the SPH could improve initiatives regarding accessibility. The event allowed us to improve levels of accessibility awareness among students and faculty walking through the SPH.

We met with multiple Deans and administration at the SPH to discuss the accessibility of the front entrance. During the meeting, we had the opportunity to understand the logistical implications of the proposal, particularly with regard to installing an accessible push-button door. The Deans and administration who work on similar initiatives provided valuable insights and recommendations on how to proceed with the proposal.

Results:

The 7-item survey consisted of six closed response questions (e.g. multiple-choice, Likert scale, and select all that apply) and one open response question. Our findings were primarily based on analyses of the results of Likert scale questions. These questions were designed with a range of response values to measure perceptions surrounding accessibility among currently enrolled Brown University students.

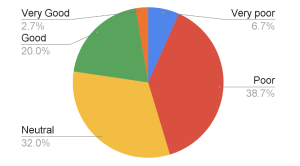

Student Perceptions on the Accessibility of Key Campus Locations:

Figure 1: Student perceptions of the accessibility of key campus locations. Using a Likert scale (1-5): Mean = 2.7; SD = 0.95

[Likert Scale: 1= Very Poor, 2 = Poor, 3 = Neutral, 4 = Good, 5 = Very Good]

We sought to gain a better understanding of how Brown students view accessibility on campus. Our survey asked students to answer the following question: How would you rate Brown’s accessibility in key locations such as academic buildings, libraries, dining halls, dorms, etc.? Students’ average ratings were “Neutral” (using a Likert scale (1-5): Mean = 2.7; SD = 0.95 [Likert Scale: 1= Very Poor, 2 = Poor, 3 = Neutral, 4 = Good, 5 = Very Good]). Less than one quarter of respondents answered that key campus locations are “very good” or “good” in regards to accessibility, whereas 45.4% of respondents characterized the accessibility of key campus locations as “very poor” or “poor.” Finally, 45.3% of respondents stated that they, or someone they know, struggle with a lack of campus accessibility measures in key campus locations.

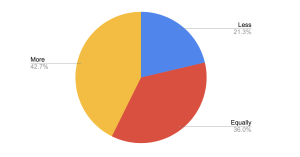

Student Perspectives on the Accessibility of Brown’s SPH vs. Main Campus:

Figure 2: Student perceptions of the accessibility of Brown’s main campus vs. Brown’s SPH Health. Using a Likert scale (1-3): Mean = 2.2; SD = 0.77

[Likert Scale: 1= Less Accessible, 2 = Equally Accessible, 3 = More Accessible]

Our project aimed to launch an initiative to increase the accessibility of Brown’s SPH, particularly the building’s front entrance. Therefore, our survey asked students to respond to the following question: “How do you expect the accessibility of Brown’s SPH buildings to compare to the accessibility of main campus Brown University buildings? Brown SPH buildings are ____ accessible” Student perceptions also fell toward “Neutral” (using a Likert scale (1-3): Mean = 2.2; SD = 0.77 [Likert Scale: 1= Less Accessible, 2 = Equally Accessible, 3 = More Accessible]). 42.7% of students in this survey indicated that they expected Brown’s SPH to be more accessible than its main campus.

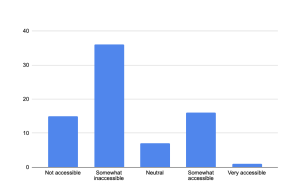

Student Perceptions on Accessibility for Individuals Utilizing Mobility Aids:

Figure 3: Student perceptions of Brown accessibility for individuals utilizing a mobility aid. Using a Likert scale: Mean = 2.3; SD = 1.1

[Likert Scale: 1 = Not Accessible, 2= Somewhat Inaccessible, 3 = Neutral, 4 = Somewhat Accessible, 5 = Very Accessible]

To further focus on the accessibility of the SPH front entrance, it was crucial for us to understand perceptions regarding the use of mobility aids. We surveyed: “How accessible do you perceive Brown to be for wheelchair users or others utilizing a mobility aid?” The results found similar neutral findings (using a Likert Scale (1-5): Mean = 2.3; SD = 1.1 [Likert Scale: 1 = Not Accessible, 2= Somewhat Inaccessible, 3 = Neutral, 4 = Somewhat Accessible, 5 = Very Accessible]). Results showed that 68% of student respondents perceive Brown’s campus to be ‘Somewhat Inaccessible” or “Completely Inaccessible” for those utilizing mobility aids. This compares to 22.6% of respondents who perceive the campus to be “Somewhat Accessible” or “Very Accessible”.

Hypothesis Tests and Further Analyses of the Data

We aimed to understand whether the mean ratings of accessibility in our responses were dependent on the following personal/interpersonal survey question: “Do you or someone you know struggle with a lack of accessibility in key campus locations?” A series of hypothesis tests were conducted to determine whether the means of the questions highlighted in the previous sections depend on participants’ responses to this personal/interpersonal question.

The difference between means for student perceptions on the accessibility of key campus locations was statistically significant when dependent on the responses to the personal/interpersonal experience question (mean student perceptions on the accessibility of key campus locations for those responding “Yes” to personal/interpersonal question = 2.265 vs. 3.122 to those responding “No”: p-value = 4.556e-05). Similarly, the difference between means regarding student perspectives on the accessibility of Brown’s SPH vs. main campus was also statistically significant when dependent on the personal/interpersonal experience response (mean student perspectives on the accessibility of Brown’s SPH vs. main campus for those that responded “Yes” to the personal/interpersonal question = 1.853 vs. 2.78 to those responding “No”: p-value = 0.0001). These findings suggest that students who have struggled or know someone who has struggled with mobility impairment on Brown’s campus are more likely to rate Brown’s accessibility lower.

Discussion:

Our results clearly demonstrated that Brown University’s accessibility measures on campus have room for improvement, considering that many students found the campus to be inaccessible in some aspects. We demonstrate that students utilizing mobility aids and those who know someone who utilizes one feel significantly stronger regarding accessibility on campus; however, overall consensus showed trends that students perceive campus to be slightly more inaccessible than accessible. Additionally, when comparing key campus locations to Brown’s SPH, perceptions leaned towards the SPH being slightly more accessible. A majority of students perceived Brown’s campus to be inaccessible for those with mobility disabilities, which demonstrates the need for advocacy and change. Furthermore, 45.3% of respondents know someone who struggles due to inaccessibility, illustrating the scope and impact that campus accessibility has on students’ university experience. Student perceptions are a testament to the fact that university administration should place an increased focus on accommodations and accessibility-related policy initiatives. Both our accessibility survey and awareness event indicate that student perceptions of Brown University’s current accommodations should be improved.

Our collaboration with administrators from the university’s SPH unveiled the bureaucratic difficulties that complicate the process of approving accommodations and expanding accessibility for students with disabilities. The Deans and administration who work on these types of initiatives provided valuable insights and recommendations on how to proceed with the proposal. The meeting proved to be an important step in ensuring that the proposed accessibility improvements are both feasible and effective.

Our project has made significant strides toward improving accessibility on campus. However, there are still various limitations to consider as we enter our next steps. Limiting our analyses were the large number of “Neutral” responses to different survey questions. To better prompt students to provide more valuable information, surveys should be developed without this response choice. Due to our convenience sampling procedure, selection bias may be a concern. Further surveys about students’ perceptions of accessibility at Brown should not only be sent out through email communications but also utilize comprehensive active forms of recruiting. Feedback from our survey suggested that future research should also consider the inclusion of other, non-mobility disabilities in the survey, which could lead to a more accurate representation of Brown’s problems with accessibility on campus.

Acknowledgments:

We would like to thank Professor Sarah Skeels for her guidance and assistance in conducting this survey and hosting our awareness event. In addition, we would like to thank PHP 1680I: Pathology to Power students Katherine Silver, Aleksa Kaye, Myrna Ortiz San Miguel, Haley Seo, Melanie Kim, Kaylah Brown, Melina Tidwell Torres, Elizabeth Ding, Iris Huang, and Jenny Tan for their help in hosting our event as well as in assisting in survey distribution. Public Health Project Committee Executive Board members Gili Schor and Madeline Day were also in PHP 1680I: Pathology to Power and facilitated collaboration between the two groups. We could not have successfully completed the project outlined without coordination between the students and faculty of the School of Public Health.

References

- What is the Americans with disabilities act (ADA)? ADA National Network. (2023, April 18). https://adata.org/learn-about-ada#:~:text=The%20purpose%20of%20the%20law,origin%2C%20age%2C%20and%20religion.

- Ripy, A. (n.d.). Building accessibility culture on college campuses. Symplicity. https://www.symplicity.com/blog/disability-services/building-accessibility-culture-on-college-campuses#:~:text=A%20lack%20of%20accessibility%20greatly,completed%20their%20degrees%20or%20certificates

- The NCES Fast Facts Tool provides quick answers to many education questions (National Center for Education Statistics). National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) Home Page, a part of the U.S. Department of Education. (n.d.). https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=60

- National Center for Education Statistics. (2011). The Condition of Education 2011 (NCES 2011-018). U.S. Department of Education. https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2011/2011018.pdf

- Ali, S. S. (2020, March 1). 30 years after Americans with disabilities act, college students say law is not enough. NBCNews.com. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/30-years-after-americans-disability-act-college-students-disabilities-say-n1138336

- Brown University. (2022). Accessibility Handbook & Guidelines. https://www.brown.edu/facilities/sites/facilities/files/01_20_01%20Accessibility%20Guidelines%2020220323.pdf