By Camille Leung

Illustration by Junyue Ma

Introduction

Half a million women around the world die every year in pregnancy, childbirth, or the six weeks following delivery; 99 percent of these deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).1 The World Health Organization’s Sustainable Development Goal 3 targets a reduction in the maternal mortality rate (MMR) to less than 70 per 100,000 live births by 2030.2 Additionally, by 2030, no country should have an MMR greater than 140–double the global target.3 This proves to be a daunting task for Indonesia, whose maternal mortality rate sits at 173 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births as of 2020 – a rate that is higher than the target goal for individual nations stated in the SDG 3.4

Indonesia, home to over 270 million people, is the world’s fourth most populous nation.5 Broadly dispersed over an archipelago of more than 13,000 islands, it is estimated that about half of the Indonesian population live in rural areas of the country.5 Considering the country’s geographic dispersion, access to skilled maternal care can be hindered, leaving expectant mothers with limited options for safe assistance during childbirth. A large number of Indonesian births occur at home, with most attended by either midwives or traditional birth attendants.6,7 Challenges in achieving a consistently safe birth process include lack of training for midwives or traditional birth attendants, inability to transport patients experiencing an emergency in a timely manner, decentralized governance and complex financing, and diverse local belief systems that cause pregnant women to often rely on fate and God’s will for a healthy pregnancy and birth.5

Midwifery is one form of birth assistance with the goal of reducing maternal mortality in both formal and informal settings. Traditional midwifery often includes practices specific to the local culture; some broad categories of care include herbal remedies, body work and movement, or spiritual routines and practices.8 In Indonesia, there is a clear local distinction between skilled midwives (bidan) and traditional birth assistants (dukun), with skilled midwives having gone through formal education to provide evidence-based care.5,8 This education is provided under the Rapid Training Program, established in 1998, a three-year midwifery program eligible for student enrollment at the end of their senior year of high school.5 Dukun often learn their skills through apprenticeship, often to a close female relative. They learn birth assistance skills, as well as ascetic practices that entail spiritual healing powers.8 Their services are utilized and respected due to trust and cultural practices in the community.9

Legal efforts have been made to formalize midwifery practices in the country, integrating them into the health care system. Local primary health centers headed by a doctor or public health official, called puskesmas, are responsible for providing antenatal and postnatal care at the sub-district level; each puskesmas may have three to five associated sub-health centers.9 At the village level, health facilities include posyandu (integrated service post), polindes (village maternity post), or poskesdes (village health post).9 To improve direct access to trained health providers, Bidan di Desa (translates to “midwife in the village”) was established in 1989, placing a trained midwife in each village along with a village birth facility (polindes).5

This evidence synthesis aims to understand and assess midwifery practices in Indonesia. It will investigate governmental programs that formally attempt to integrate midwives into the healthcare system, evaluate perceptions of different forms of midwifery (skilled and traditional), and explore the different ways in which traditional birth assistants (dukun) provide care that is influenced by local cultural practices and beliefs. In identifying gaps in knowledge and context for birthing practices in Indonesia, this paper hopes to suggest perspectives and solutions that can guide future studies or interventions that improve the nation’s maternal health.

Methods

In conducting a literature review, PubMed was utilized to search for relevant papers on this topic. Selected literature was managed using Zotero. The search string used is found in the Appendix. Keyword selection involved several considerations. Running a search containing just “Indonesia”, as opposed to “in Indonesia”, yielded many irrelevant results, including any and all papers that mentioned the country. Limiting the search using “in Indonesia” ensured that reviewing literature that investigated midwifery was specific to Indonesia. To capture any papers discussing traditional midwifery practices, the keywords “midwif*” and “traditional” were searched with. Two filters were used to refine the search: one to include papers written in English and another to focus on publications from the year 2000 onwards. The time constraint retains more recent data, providing insights into the current status of maternal mortality in the country. The PubMed search generated 16 results, 12 of which were retained. three results were excluded due to lack of focus on midwifery practices, and one study was excluded for having a focus on midwifery practices at the global level. One additional search with the same filters was done to gather more information on traditional antenatal care, which generated 16 results. Of the 16 results, 7 studies were excluded for having no relation to the topic, and an additional 7 studies were excluded for redundancy. Two studies were retained in this second search. A review of the studies selected for review is found in the Appendix (Figure 1).

Results

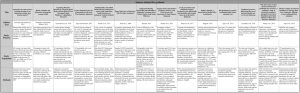

The overview of studies selected for synthesis in Figure 1 showcases each study’s design, population, and methods. This should serve as background context that frames the general findings that will be discussed in this section. Much of the literature contains personal interviews and accounts of mothers’ experiences with antenatal care, childbirth, and postnatal care to better understand local perceptions and traditions as it relates to maternal care.

This paper will discuss select notable trends in the literature: perceptions of childbirth, safety, and cultural practices, barriers to maternal care, characteristics of traditional antenatal care, and challenges to integrative care between skilled and traditional midwives.

Perceptions of childbirth, safety, and cultural practices

In Indonesia, especially in rural areas of the country, childbirth occurring at home is incredibly prevalent.6,7,10 The government has made attempts to lower the country’s maternal mortality rate by covering pregnant women under the national health insurance that would allow them free access to local health centers staffed by skilled birth assistants; additionally, initiatives such as Bidan di Desa aim to foster partnerships between skilled and traditional midwives.11,12 Despite this, freebirth continues to occur at high rates, largely with traditional birth attendants or untrained family members; the complications and maternal outcomes associated with these births often go unrecorded due to weak vital registration systems.11 A study from rural West Java interviewed mothers who voiced that pregnancy and delivery are viewed as natural processes that would occur with or without assistance; as such, danger signs were not anticipated or monitored.1

Several factors contribute to a mother’s choice in location of birth. Many mothers interviewed considered the home a safe location for birth, in contrast to the “threatening” demeanor of a health facility.7,11,13 Additionally, the home is perceived to be a spiritually nourishing location –an idea passed down through generations– guaranteeing a successful birth.7,11 Factors that increased the likelihood of a mother to seek out birth assistance from a trained provider included having a maternal education, having a higher income, living in an urban area, and having over four antenatal visits.7,10,14 When mothers choose between skilled and traditional methods of birth assistance, several factors play a role. Women who had less education, were multiparous, lived in an area with higher density of traditional birth assistants, and had a lack of health insurance were likelier to select a traditional birth assistant.10,14 Family members, particularly the mother’s husband or mother-in-law, have a strong influence in a woman’s choice to seek maternal care.14 The study led by Agus, Horiuchi, and Iida in 2018 found that nearly half of the mothers who sought birth assistance from a traditional birth assistant were encouraged by their mothers to do so.14 Many of these country-wide trends were reflected in the smaller case study of the rural Riau Province, but with additional language and religious barriers that led mothers to feel alienated by surrounding communities; these mothers also felt desires to keep with their local traditions that only their family members and traditional birth assistants understood – one example being the washing and wrapping of the mother’s placenta after birth.11

Barriers to maternal care

The country’s geographic dispersion, as mentioned earlier, poses a large barrier in the government’s ability to sponsor equitable, accessible healthcare. The Indonesian Ministry of Health serves as the country’s main health policymakers, with local governments given the responsibility of managing their own health policies.12 This decentralization of healthcare governance was studied by Pardosi et al. in 2016, where it was found that many remote villages had either a shortage or complete absence of midwives and other childbirth-related staff.12Many mothers reported having to walk long distances –one or two hours worth of walking–in order to reach the nearest healthcare facility.9,15,16 The Ministry of Health requires that there be at least four facilities per district that can provide obstetric services; as of 2011, only 61 percent of districts met this minimum requirement.15

A mother’s financial status proves to be a significant barrier in her ability to seek care. Low-income mothers expressed finding traditional birth assistants to be a cheaper alternative, and had a general hesitancy to pay additional costs for transportation.8,9,15 Additionally, misconceptions about eligibility for coverage and services provided under insurance programs like Jamkesmas (a government-run public insurance program that covers the country’s poor) led women to not only have false understanding of where the coverage could be used, but also to believe that the best services would only be provided from facilities where payment was necessary.9,15 Though one study showed that women who had Jamkesmas were 19 percent likelier to deliver in a health facility, it was noted that many other barriers such as sociocultural beliefs and accessibility of care must be addressed to make a significant difference in lowering the country’s MMR.15

There exists a lack of maternal health education and trained health staff, ultimately affecting quality of care. Accreditation of healthcare facilities, which would guarantee a national standard of care, is not a fully implemented system in Indonesia.15 Health staff have incomprehensive training, leaving them with inadequate skills and knowledge to provide hygienic and safe support during delivery.12,15 When maternal healthcare staff were available, plenty of examples were shown where midwives and nurses would refuse to provide services to mothers in need at late hours, or because they simply did not have a close relationship to the mother.12 Mothers themselves did not hold informed views on their own health, and would not seek out antenatal or postnatal care so long as they felt healthy.9,16 Some of the literature advocates for women to be fully informed of the danger signs during pregnancy, especially as almost half of primary or secondary-educated women reported not receiving information about pregnancy during their education.1,16

Social factors can affect a mother’s ability to seek care. It is mentioned earlier that family members have a say in determining a mother’s method of birth assistance.14 This is in line with findings that recognize gender inequity issues in the country that keep women in a submissive position relative to their husbands.1,16 Additionally, women who participated in traditional antenatal practices, whether by choice or by social pressure, were less likely to seek out antenatal care from formal health facilities.9,16

Characteristics of traditional antenatal care

Many mothers prefer assistance from a traditional birth assistance due to the trust that is built by local respect, speaking the local language, and sharing similar cultural backgrounds.1,9,15 Additionally, higher numbers of traditional birth assistants in especially rural areas often makes it the more accessible and preferred method of birth assistance.6,10,16

Traditional birth assistants receive training that is passed down from generation to generation.11,13 It is said that this knowledge lives and dies with the midwife until the practices are passed on to an apprentice.13 One study in 2016 interviewed traditional birth assistants (belian) in the Lombok region, and each belian had reported being an apprentice to a senior belian in their bloodline in their training.13 The study investigated the experiences of belians who underwent government-based midwife training programs, with the majority participating. However, it was discovered that the training was somewhat irrelevant to traditional midwifery, as participants were already familiar with certain aspects of the education provided (e.g., signs of high-risk pregnancies); there was additionally a noted absence of a consistent supply of modern medical tools recommended for use.13

The traditional practices involved come in many forms ranging over a large variety of modes, including diet, body movement, remedies, and more.9,17 Vegetables were believed to be better for a pregnant woman’s diet because they freshen the taste of breastmilk.17 It was warned that the discouragement of eating meat could be dangerous, as meat promotes iron absorption, which can offset risks for anemia.17 Massages were mentioned as an important ritual for mothers, occurring at different points during a woman’s pregnancy.9,13 These massages were sometimes used to determine aspects of the medical condition of the pregnancy–for example, to determine the baby’s position – to overcome infertility, or to maintain a mother’s general health during pregnancy.9,13 Herbal remedies, perceived to be more “natural” than modern medicine and without side effects, are also used to keep mothers healthy; one paper discussing herbal remedies was unable to clarify the justification for the herbal remedies as their purpose was kept secret and exclusive to the belians.13,17 In terms of attitudes, women expressed both an internal and external locus of control, indicating a willingness to follow recommended health practices while recognizing that the ultimate fate of their delivery and baby would be determined by God.1,17,18

Challenges in integrative maternal care

Given the different approaches to maternal health that coexist in the country, there are differing opinions on the effectiveness of traditional methods. The dangerous sentiments surrounding practices celebrated by dukun have ties that run back as far as Dutch colonists’ attempts to modernize medicine.8 Dukun are respected in their local communities but are underappreciated by biomedical and public health professionals.8 The government views dukun as a threat to medicalization of birth, but simultaneously recognizes that dukun allows for access to care in remote villages.8 Efforts such as Bidan di Desa have been used by the government to formalize midwifery access and quality of care, and to establish a working partnership between bidan and dukun.5,8 Under this program, the bidan’s role had no need to take on new responsibilities; the dukun, however, was asked to take on more of an “assistant” role to the bidan by encouraging mothers to use services provided by bidan, assist the bidan with pre-natal checkups and birthing, and perform healthy ritual services when requested.8 This effectively formalized the inferiority of the dukun to the bidan in both knowledge and power, and recognized spiritual exercises as a secondary focus of care, only given upon request.8

The literature presents mixed accounts regarding satisfaction with care. A study examining perceived satisfaction with care revealed that women who chose midwives reported significantly higher satisfaction scores compared to those who opted for traditional birth assistants.14 This study also noted that more than 70 percent of women in Indonesia experience delays in seeking and receiving care; when such interruptions occurred, traditional birth assistants were called.14 This is in agreement with the observation that a higher density of traditional birth assistants in an area decreases the chances that a woman will receive maternal care or services.10 Several studies have suggested that traditional birth assistants are characterized by greater tolerance, patience, and experience compared to midwives.1,8,14 In other interviews, some women emphasized the importance and sense of security associated with the medical professionalism of midwives over that of traditional birth attendants.1

Discussion

The available literature presents various perspectives on the role of midwifery in addressing Indonesia’s maternal mortality rate with SDG 3 in mind. Diverse cultural practices and varying levels of access to care make approaches to this goal challenging. Four main themes arise from the literature: structural barriers when it comes to access to and quality of care, the coexistence and tensions between skilled and traditional birth assistants and the push for skilled midwifery to be a primary mode of maternal healthcare when possible, and competing arguments for and against traditional birth assistant utilization.

Costs, geographic dispersion, and perceptions of care all influence healthcare utilization choices. Though more superior in its medical quality, skilled midwifery can be inaccessible and pricey for low-income mothers. Additional considerations, such as transportation costs and safety, make services provided by skilled medical professionals further out of reach. Traditional birth assistants are often the more affordable and accessible option, especially in remote areas. Skepticism of the hospitality offered by medical facilities, coupled with the personalized nature of the services given exclusively by traditional birth assistants can push mothers towards selecting a traditional birth assistant over a skilled one. These barriers are intertwined and reinforce one another, and require a multifaceted approach in overcoming them.

Tensions between skilled midwives and traditional birth assistants extend beyond the pure differences between their approaches to maternal care; they are delineated and exacerbated through legislative and behavioral undercurrents. This is evident in the literature, whereas traditional birth assistants are not granted the official term of “midwife” in multiple papers. Even moreso, the Indonesian language uses “bidan” and “dukun” to separate these two forms of midwifery, with the latter translating to “witch doctor” in English. Traditional birth assistants have garnered much respect in their local communities for their ancestral wisdom and birth rituals. As the government makes pushes to establish training programs for midwives, traditional birth assistants are left to find roles that are subordinate to the midwife. The rise of the medical professionalization of the midwife serves as a threat to the livelihood of traditional birth assistants. The coexistence of these two groups necessitates a balance; there is a need to respect and understand the traditions led by traditional birth assistants, while also ensuring that childbirth is a safe process–a task that skilled midwives are more equipped to handle.

The literature showcases some competing opinions on whether traditional midwifery should be utilized to a greater extent to battle the MMR. Some papers more clearly advocated for increasing the number of births occurring in a health facility with skilled midwives and trained health workers.10,11 Other authors were more empathetic in understanding the importance and accessibility of traditional birth assistants.8,13,17 It is found that while traditional birth assistants are more affordable, patient and comforting, and more accessible, they also do not guarantee the better quality of care, maternal health outcomes, and better training that are associated with skilled midwives. A nuanced approach should be taken when comparing these two options for maternal care. A push for all births to occur in health facilities, while ideal and effective in guaranteeing a standard quality of care, may not be feasible for the considerable proportion of the population that lives in rurality. In a country where healthcare access is unequal across the population, there ought to be consideration on how to better utilize the abundance of traditional birth assistants operating in the country’s most remote areas.

There are several limitations to address in this synthesis. Because traditional midwifery practices are carried through generations, these practices may not have been comprehensively documented or accurately preserved, especially within the search’s selected time range. Moreover, several studies that involved interviews with traditional birth assistants noted the secrecy of some of their beliefs and practices; as such, there are further gaps in the working knowledge of traditional practices.13,17 On a broader scale, traditional practices in midwifery remain understudied, with limited literature exploring this topic. During the initial literature search, several articles describing traditional practices written in Bahasa, without translation; additional limitations arise when considering that the synthesis was restricted to literature written in English.

Gaps in the literature still persist in this area. There is still much to be learned about the practices involved in traditional midwifery. Efforts to discern the underlying reasons for specific practices proved futile, as traditional birth assistants were determined to safeguard their healing secrets.13,17 Consequently, delving into research aimed at unraveling these traditions would provide new insights to consider in evaluating traditional methods. Additionally, it is still not fully understood whether programs like Bidan di Desa have been effective in integrating care between bidan and dukun, as well as improving maternal health outcomes. These findings would be crucial in knowing whether these efforts are worth scaling up in its enforcement country-wide.

Conclusion

This synthesis hopes to help bridge a gap in knowledge regarding traditional and skilled approaches to midwifery in Indonesia. The advocacy and use of skilled midwifery to combat the maternal mortality rate is seen through government-led training modules and programs like Bidan di Desa. Traditional methods of midwifery are deeply rooted in cultural beliefs and are driven by accessibility, affordability, and trust. However, challenges such as geographical dispersion, financial constraints, limited access to education, and gender inequities persist, complicating the pursuit of improved maternal health. Competing opinions regarding the value of care that traditional birth assistants provide further complicates options for what an ideal path forward might look like.

In looking towards recommendations for future research, it should be investigated whether the empowerment of traditional midwifery, when medically safe, backed by scientific evidence, and culturally sensitive, can improve maternal health outcomes for women living in areas that do not have ready access to proper healthcare facilities. The increased utilization of traditional birth assistants has potential to be particularly impactful, as they are already trusted figures in their local communities.1,9,15 Interventions should be practiced in a community-led manner, involving collaborative efforts between researchers and local stakeholders to ensure the effectiveness and sustainability of such initiatives. If it is determined that enhancing the skills and education of traditional birth assistants is effective, there could be significant implications for improving access to maternal care that is trustworthy, high quality, and accessible to all.

While Indonesia has made strides in improving maternal health through midwifery, there remains significant room for improvement. A balanced approach that respects traditional practices while promoting evidence-based healthcare will be instrumental in further reducing maternal mortality rates in Indonesia.

Bibliography

- Agus Y, Horiuchi S. Factors influencing the use of antenatal care in rural West Sumatra, Indonesia – BMC pregnancy and childbirth. BioMed Central. February 21, 2012. https://bmcpregnancychildbirth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2393-12-9.

- SDG target 3.1: maternal mortality. World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/indicator-groups/indicator-group-details/GHO/maternal-mortality#:~:text=SDG%20Target%203.1%20%7C%20Maternal%20mortality,per%20100%20000%20live%20births.

- Ending preventable maternal mortality (EPMM). World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/initiatives/ending-preventable-maternal-mortality.

- Indonesia profile page. UNICEF DATA. February 9, 2023. https://data.unicef.org/countdown-2030/.

- Reducing maternal and neonatal mortality in Indonesia: Saving lives, saving the future. National Center for Biotechnology Information. December 26, 2013. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24851304/#:~:text=Reducing%20Maternal%20and%20Neonatal%20Mortality%20in%20Indonesia%20is%20a%20joint,achieve%20the%20Millennium%20Development%20Goals.

- Ansariadi, Manderson L. Antenatal care and women’s birthing decisions in an Indonesian setting: Does location matter? Rural and Remote Health. June 8, 2015. http://www.rrh.org.au/journal/article/2959.

- Thind A, Banerjee K. Home deliveries in Indonesia: Who provides assistance? – journal of community health. SpringerLink. August 2004. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1023/B:JOHE.0000025327.70959.d3.

- Magrath P. Right to health: A buzzword in health policy in Indonesia. May 1, 2019. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/01459740.2019.1604701.

- Titaley CR, Hunter CL, Heywood P, Dibley MJ. Why don’t some women attend antenatal and postnatal care services?: A qualitative study of community members’ perspectives in garut, sukabumi and Ciamis districts of West Java Province, Indonesia – BMC pregnancy and childbirth. BioMed Central. October 12, 2010. https://bmcpregnancychildbirth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2393-10-61.

- Aryastami NK, Mubasyiroh R. Traditional practices influencing the use of maternal health care services in Indonesia. PLOS ONE. September 10, 2021. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0257032.

- Kusumawati N, Erlinawati E, Safitri Y, Nurman M, Erlin F. Exploring women’s reasons for choosing home birth with the help of their untrained family members: A qualitative research. International Journal of Community Based Nursing & Midwifery. April 1, 2023. https://ijcbnm.sums.ac.ir/article_49161.html.

- Pardosi JF, Parr N, Muhidin S. Local Government and Community Leaders’ Perspectives on Child Health and mortality and inequity issues in rural Eastern Indonesia: Journal of Biosocial Science. Cambridge Core. April 29, 2016. http://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-biosocial-science/article/local-government-and-community-leaders-perspectives-on-child-health-and-mortality-and-inequity-issues-in-rural-eastern-indonesia/05634DF3DB43B3FE086D5172D34F7C77.

- Bennett LR. Indigenous healing knowledge and infertility in Indonesia: Learning about Cultural Safety from Sasak Midwives. Medical Anthropology: Cross-Cultural Studies in Health and Illness. March 17, 2016. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/01459740.2016.1142990.

- Agus Y, Horiuchi S, Iida M. Women’s choice of maternal healthcare in Parung, West Java, Indonesia: Midwife versus traditional birth attendant. Women and Birth. February 14, 2018. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1871519217301452?via%3Dihub.

- Brooks MI, Thabrany H, Fox MP, Wirtz VJ, Feeley FG, Sabin LL. Health facility and skilled birth deliveries among poor women with Jamkesmas Health Insurance in Indonesia: A mixed-methods study. BioMed Central. February 2, 2017. https://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12913-017-2028-3.

- Pardosi JF, Parr N, Muhidin S. Inequity issues and mothers’ pregnancy, delivery and early-age survival experiences in Ende District, Indonesia: Journal of Biosocial Science. Cambridge Core. December 15, 2014. http://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-biosocial-science/article/abs/inequity-issues-and-mothers-pregnancy-delivery-and-earlyage-survival-experiences-in-ende-district-indonesia/C66145FE1C6D6D7F58310DE1729CE84D.

- Wulandari LPL, Klinken Whelan A. Beliefs, attitudes and behaviours of pregnant women in Bali. Midwifery. December 4, 2010. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0266613810001488?via%3Dihub.

- Agus Y, Horiuchi S, Porter SE. Rural Indonesia women’s traditional beliefs about antenatal care. BioMed Central. October 29, 2012. https://bmcresnotes.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1756-0500-5-589.

Appendix

Search strings used:

“midwif*” AND “in Indonesia” AND “traditional”

“traditional” AND “antenatal” AND “indonesia”

Figure 1. Sources reviewed for synthesis.